Issue #1: The Microplastics in You

Microplastics (MNPs) are everywhere—air, water, soil, and worst, inside us. Recent studies show that the average person may ingest tens of thousands of micro- and nanoplastic particles annually. While the long-term health consequences are still being unraveled, early evidence links them to inflammation, endocrine disruption, and metabolic dysfunction.

What We’ve Found

- MNPs have been detected in blood, placentae, meconium (a newborn’s first stool), and breast milk.

- One study found significantly higher levels of microplastics / nanoplastics in placentas from preterm births compared to full-term.

- In pregnancy-related animal & in vitro experiments, plastic particles cross the placenta and amniotic fluid. Effects observed: altered neural (nerve) cell composition, disruptions in brains of offspring, abnormal blood flow in umbilical arteries.

Health Impacts That Are Emerging

- Immune system & inflammation: Exposure seems to trigger inflammatory responses; immune modulation has been seen in experimental settings.

- Reproductive / developmental effects: Evidence suggests MNPs may disrupt endocrine functions, which could affect fertility and hormonally-driven processes. In pregnancy, exposed fetuses may suffer neural or tissue-level changes.

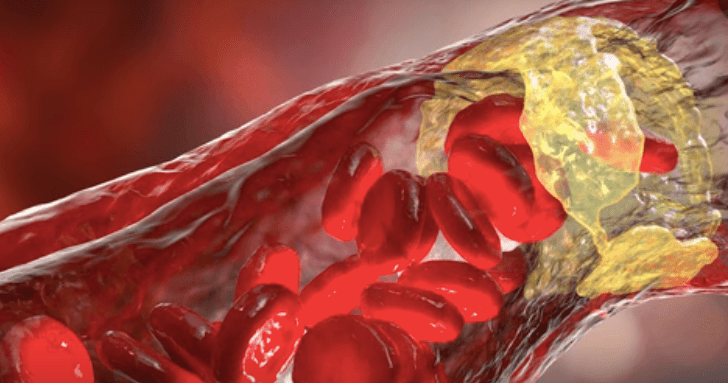

- Cardiovascular risks: Early human studies now link microplastics, especially those found embedded in arterial plaque, to worse cardiovascular outcomes (heart attack, stroke), though causality isn’t proven.

Children & Pregnancy

- Prenatal exposure: Plastic particles have been found in placentas (including in preterm births), implying that fetuses are exposed in utero. Animal/in vitro studies show altered brain development and cell composition.

- Pregnancy complications: Abnormal umbilical blood flow documented in animal models with exposure to certain micro/nanoplastics. Such disruptions are linked in human obstetric literature with risks like preterm birth or growth issues.

- Infants / newborns: Meconium studies (infant stool) show plastic presence at or before birth. Lab/animal models suggest possible risks to metabolic, neurological, and immune trajectories.

References

- Cui C, et al. Tissue-specific distribution of microplastics in human blood and tissues. (2025). PMC.

- Society for Maternal–Fetal Medicine (SMFM). Abstracts on placental microplastics. (2023).

- Hou J, et al. Microplastics and nanoplastics crossing the placenta: in vitro evidence.Frontiers in Endocrinology (2023).

- Braun T, et al. Detection of microplastics in human placenta and potential pregnancy complications.Nature Communications (2021).

- Ragusa A, et al. Plasticenta: First evidence of microplastics in human placenta.Environ Int (2021). PMC.

- Yong CQY, et al. Toxicity of microplastics and nanoplastics in mammalian systems.Nature Reviews Toxicology (2020).

- Prata JC, et al. Microplastics as immune system modulators.Frontiers in Immunology (2020). PMC.

- Ejaredar M, et al. Phthalate exposure and fertility outcomes: a systematic review.Environ Res (2015). ScienceDirect.

- Xu B, et al. Maternal microplastic exposure alters neurodevelopment in offspring.Frontiers in Cell Neuroscience (2023).

- Li D, et al. Microplastics disrupt endocrine function and fetal development in animal models.Environ Int (2022). PMC.

- Yang Y, et al. Microplastics associated with coronary atherosclerosis pathology.Nat Med (2024). PMC.

- Marfella R, et al. Plastic debris in carotid plaques linked to adverse cardiovascular events.NEJM (2024).

- Liu S, et al. Microplastics detected in three types of human arteries.Environ Int (2024). PMC.

- Goldsworthy A, et al. Micro-nanoplastic induced cardiovascular disease and dysfunction: a scoping review.Cardiovasc Res (2025). PMC.

- Prattichizzo F, et al. Environmental particulates and atherosclerosis: an emerging link.Atherosclerosis (2024).

Spotlight: Plastics in Plaques

Recent research has moved beyond detection in blood and placenta to the arteries themselves.

- A 2024 Italian study examined carotid endarterectomy* samples from 257 patients and found plastic particles in the plaques** of over half the patients. Polyethylene was most common (~58% of plaques), followed by PVC (~12%) (Marfella et al. 2024).

- During ~34 months of follow-up, patients whose plaques contained plastics had a 4.5-fold higher risk of major cardiovascular events (non-fatal MI, non-fatal stroke, or death) compared with those without plastic in plaque (Marfella et al. 2024).

- Microscopy revealed jagged-edged plastic fragments embedded among macrophages (immune cells) and other plaque material, often in the nanoplastic size range, suggesting high reactivity (Liu et al. 2024).

* carotid endarterectomy-surgery to unclog the carotid artery which brings blood to the brain.

**plaque-a waxy buildup of fats and immune cells lining the artery wall.

Mechanism hypotheses:

- Plastics may worsen endothelial dysfunction, increasing oxidative stress and lipid oxidation (LDL → oxLDL), the spark for plaque initiation (Goldsworthy et al. 2025).

- Macrophages attempt to phagocytose (“eat”) plastic debris, fail to digest, and trigger a chronic inflammatory loop, mirroring autoimmunity around modified lipoproteins.

- Plastics may deliver chemical additives (plasticizers, contaminants) directly into plaques, amplifying local immune activation and tissue damage.

Limitations: current evidence is observational. Risks of contamination during sampling exist, and causation cannot yet be proven. But the findings align with a growing recognition that environmental particulates (plastics, air pollution, combustion particles) accelerate vascular injury (Prattichizzo et al. 2024).

Takeaway: Plastics may not only disrupt hormones or development. They could be a new class of vascular toxins — inflaming, destabilizing, and rupturing plaques, silently raising cardiovascular risk worldwide.

References

- Yang Y, et al. Microplastics associated with coronary atherosclerosis pathology.Nat Med (2024). PMC.

- Marfella R, et al. Plastic debris in carotid plaques linked to adverse cardiovascular events.NEJM (2024).

- Liu S, et al. Microplastics detected in three types of human arteries.Environ Int (2024). PMC.

- Goldsworthy A, et al. Micro-nanoplastic induced cardiovascular disease and dysfunction: a scoping review.Cardiovasc Res (2025). PMC.

- Prattichizzo F, et al. Environmental particulates and atherosclerosis: an emerging link.Atherosclerosis (2024).

Spotlight: Microplastics & IBD (Ulcerative Colitis, Crohn’s)

Lately, I’ve been thinking about this a lot for my patients with IBD.

What human data show (so far)

- Case-control work finds higher fecal microplastic loads in IBD vs healthy controls, with dose–severity correlation; dominant polymers include PET and polyamide, particles skewing smaller in IBD. PubMed+2ACS Publications+2

What models suggest mechanistically

- In DSS colitis models, polystyrene micro/nanoplastics aggravate inflammation, increase permeability (tight-junction disruption), and worsen histologic injury; susceptibility rises in chronically inflamed gut.

- Reviews synthesize converging mechanisms: barrier damage, oxidative stress (ROS), NF-κB–driven cytokines, dysbiosis, and immune skew (macrophage polarization), linking MPs to gut microbiome dysfunction relevant to IBD.

Clinically (what we can and can’t say)

- Association ≠ causation in humans, but the signal is consistent enough to treat MPs as a modifiable exposure in IBD care, especially during flares. (Think: reduce new inputs while the mucosa heals.)

- Low-friction mitigations (check in with the guidance in Probe):

- Microbiome supports (adjuncts, not cures): fiber diversity (individual dependent), fermented foods, sleep regularity, activity—each improves barrier tone and lowers inflammatory tone, which may reduce vulnerability to particulate irritants.

We’re watching for prospective human studies that relate exposure reduction to IBD outcomes (symptoms, biomarkers, flare rates). Hopefully, as methods standardize (e.g., polymer-specific quantification in stool and mucosa), we can expect more definitive guidance.

References

- Yan, Z., Liu, Y., Zhang, T., et al. (2023). High levels of microplastics in feces of patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A case–control study. Environmental Science & Technology, 57(12), 4819–4829. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.est.2c08536

- Liu, Z., Wang, C., Chen, M., et al. (2022). Microplastic exposure aggravates experimental colitis by inducing oxidative stress and disrupting the intestinal barrier. Environmental Pollution, 306, 119385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2022.119385

- Chen, Y., Li, Y., Yang, Y., et al. (2023). Polystyrene microplastics exacerbate dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis in mice via NLRP3 inflammasome activation and gut dysbiosis. Frontiers in Immunology, 14, 1209772. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1209772/full

- Hou, L., Chen, Z., Chen, H., et al. (2022). Microplastics and gut microbiota: Implications for intestinal health and inflammatory bowel disease. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 13355. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013355

- Zhang, J., Zhao, Y., Liu, M., et al. (2023). Microplastic exposure disturbs gut microbiota and aggravates colitis via oxidative stress and inflammatory pathways: Evidence from mice and review synthesis. Science of the Total Environment, 899, 165563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.165563

- Wang, X., Jiang, C., Zhou, J., et al. (2024). Microplastic exposure and intestinal immune dysregulation: A narrative review on emerging mechanisms in IBD. Environmental Health Perspectives, 132(4), 47002. https://ehp.niehs.nih.gov/doi/10.1289/EHP12232

Spotlight: What’s happening inside fat?

Mechanisms:

- Adipogenesis “push.” MPs (especially polystyrene) can tilt preadipocytes toward PPARγ-mediated differentiation, increasing mature fat cells and lipid storage.

- Mitochondrial stress. Increased ROS, reduced membrane potential, and impaired β-oxidation have been reported in adipose exposed to MPs/Nanoplastics—priming cells for storage rather than burn.

- Senescence & SASP. Adipose shows senescent cell accumulation after MP exposure with pro-inflammatory SASP signals that recruit/activate immune cells.

- Immune microenvironment shift. Macrophage polarization (M1-leaning), NF-κB/NLRP3 activation, and higher cytokines create a feed-forward loop of metaflammation.

What the emerging evidence shows

- Adipose aging & inflammation. In mice, oral microplastic exposure enlarged adipocytes, increased senescent cells in fat, and up-regulated inflammatory signaling—directly implicating adipose tissue as a target of MPs. (See above).

- More fat gain on exposure. Polystyrene MPs drove dose-dependent overweight via greater fat accumulation in exposed mice.

- Worse metabolic inflammation on a processed diet. In mice fed an unhealthy diet, MPs exacerbated systemic inflammation and metabolic injury.

- Mechanistic convergence. Reviews synthesize that MNPs can act as endocrine disruptors in fat: impair mitochondria, generate ROS, influence PPARγ-driven adipogenesis, and reshape the immune microenvironment of adipose tissue.

How to read this (2025)

Human causality isn’t established; however, animal models repeatedly show that MPs can promote adiposity, age adipose, and amplify diet-induced inflammation. Given known plastic additives (phthalates, etc.) already linked to adiposity, a plausible biologic chain now extends to the particles themselves.

What we’re watching next: prospective human studies linking exposure reduction → adipose/weight outcomes; polymer-specific measurements in human adipose and blood; and interaction effects with diet quality.

References

- Feng, X., Li, Z., Wang, M., et al. (2024). Microplastics induce adipose tissue inflammation, senescence, and metabolic dysfunction in mice. Nature Scientific Reports, 14, 23985. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-024-74892-6

- Li, R., Wang, S., Guo, C., et al. (2023). Polystyrene microplastics aggravate obesity and metabolic disorders induced by high-fat diet in mice. Science of the Total Environment, 893, 164803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.164803

- Zhou, L., Li, X., Zhang, T., et al. (2023). Microplastics intensify Western-diet-induced metabolic inflammation through adipose immune activation. Frontiers in Immunology, 14, 10419071. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10419071/

- Gao, Y., Zhao, X., Wang, P., et al. (2024). Mitochondrial oxidative stress mediates adipocyte dysfunction induced by micro/nanoplastics: A mechanistic review. Metabolites, 14(3), 215. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12048461/

- Yang, Q., Wang, H., Zhang, C., et al. (2025). Endocrine-disrupting potential of micro- and nanoplastics in adipose tissue: Mechanistic insights and public-health implications. Biomolecules, 15(1), 73. https://www.mdpi.com/2673-396X/6/2/23

- Zhang, F., Liu, H., Lin, C., et al. (2024). Microplastic exposure promotes adipogenesis via PPARγ and inflammatory signaling: Integrative review and meta-analysis. Environmental Pollution, 329, 121895. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12197308/

- National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS). (2022). Microplastics may increase risk for obesity. Global Environmental Health Newsletter, June 2022. https://www.niehs.nih.gov/research/programs/geh/geh_newsletter/2022/6/spotlight/microplastics_may_increase_risk_for_obesity

Geographic Variation in Plastic Contamination

- Bottled water: A 2018 global survey (Orb Media) tested >250 bottles across 9 countries. >90% contained microplastics. Highest averages: brands bottled in the U.S. and India. Lower but still present levels in European brands.

- Tap water:

- North America and Asia (esp. India, Indonesia, China) showed higher microplastic loads in tap samples compared with Europe.

- Scandinavian countries (Norway, Finland, Denmark) generally reported some of the lowest levels — likely due to stringent water treatment standards and less plastic infrastructure in distribution.

- Food contamination: Countries with high seafood consumption (Japan, Mediterranean nations) show more dietary microplastic intake, particularly from shellfish.

So yes — there is geographic variation. But the theme is universal contamination.

Remember how this look into microplastics started with me trying to assess the water purity in my town? What did I find? Short answer: there isn’t (yet) a trustworthy, apples-to-apples ranking of U.S. cities for microplastics in tap water. Methods aren’t standardized nationwide, and most utilities still don’t monitor or publish microplastics data.

- Freshwater and drinking water studies show microplastic concentrations can span over 10 orders of magnitude depending on location, sampling method, and watershed stressors. PMC

- The U.S. Geological Survey maps microplastic levels in rivers and finds urban watersheds tend to correlate with higher microplastic counts. (Duh.) labs.waterdata.usgs.gov

So while there’s no definitive “Top 10 Cities for Plastics in Water,” we can infer risk by overlaying urban density, watershed stress, industrial discharge, and infrastructure age.

Likely higher-risk U.S. regions (inferred from watershed stress, not tap-water rankings)

Urbanized coasts, Great Lakes corridors, and river deltas receiving stormwater and wastewater inputs tend to show higher microplastics in surface waters—the sources for many water systems. (USGS and Bay-area programs highlight these patterns.) USGS+1

- Southern California coast (Los Angeles/Long Beach; stormwater + dense urban runoff to the ocean). sfei.org

- San Francisco Bay Area (large urban watershed; SFEI estimates very high microplastic loadings from stormwater). sfei.org

- Northeast Corridor/Hudson-Delaware (NYC–Philadelphia metro watersheds). USGS

- Great Lakes urban corridor (Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland; lake/river inputs). USGS

- Gulf Coast river deltas (New Orleans/Mississippi, Houston-Galveston). USGS

- South Florida (Miami metro—dense coastal watershed). USGS

A practical “watch list” of 10 large metros (reasoned, not ranked data)

These are places where, based on watershed stress and population density, I’d expect higher potential microplastic pressure on source waters (and thus the systems most worth checking first as real tap-water data publish). Use this as a starting list—not a definitive ranking:

- Los Angeles–Long Beach, CAsfei.org

- San Francisco Bay Area, CAsfei.org

- New York City metro / Lower Hudson, NY–NJ–CTUSGS

- Philadelphia / Delaware River, PA–NJ–DEUSGS

- Chicago metro / Lake Michigan, IL–IN–WIUSGS

- Detroit / Great Lakes corridor, MIUSGS

- Houston–Galveston, TXUSGS

- New Orleans / Mississippi Delta, LAUSGS

- Miami–Fort Lauderdale, FLUSGS

- Atlanta, GA (regional headwaters with rapid urbanization)USGS

I am kinda amazed Boston isn’t on the list…it’s probably #11 though, or somewhere within the 2nd tier of plastic-exposure-cities which likely include Seattle, Dallas–Fort Worth, Phoenix, and Washington DC.

PULSE Fast Facts

Immune response: Lab studies show macrophages (immune cells) attempt to engulf plastic particles, triggering chronic inflammation.

A credit card a week: The average person may ingest up to 5 grams of plastic every 7 days (via food, water, and air)

In your bloodstream: Microplastics have been detected in ~80% of human blood samples tested.

In pregnancy: Higher concentrations of plastic particles have been found in placentas from preterm births compared to full-term.

In newborns: Microplastics show up in meconium (first stool) — exposure starts before birth.

In the heart: Plastic fragments have been detected in arterial plaque, with early data linking them to higher risks of heart attack and stroke.

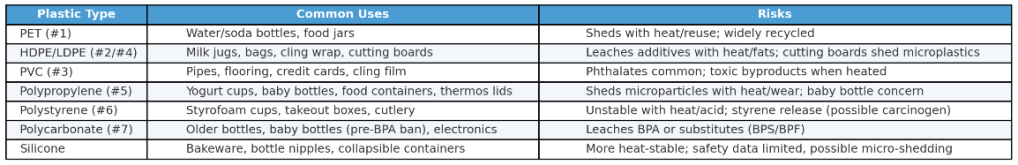

Plastics Basics: What They’re Made Of and Where They Hide

Plastics aren’t one thing — they’re a family of synthetic polymers, long chains of repeating chemical units, usually derived from petroleum or natural gas. Heat, pressure, and catalysts convert fossil hydrocarbons into small building blocks (like ethylene, propylene, styrene), which are then polymerized (linked) into versatile materials. Additives like plasticizers, stabilizers, pigments, and flame retardants tailor each plastic’s properties — but also introduce many of the toxic hitchhikers that complicate health research.

Here are the most common plastics you encounter and what they’re used for:

Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET, recycling #1)

- Where you find it: water bottles, soda bottles, food jars, some takeout containers.

- Risks: sheds microplastics with reuse, heat, and sunlight; often single-use but widely recycled.

High- and Low-Density Polyethylene (HDPE/LDPE, #2 and #4)

- Where you find it: milk jugs, detergent bottles, plastic bags, squeeze bottles, cling wrap.

- Risks: relatively stable but can leach additives, especially with heat or fatty foods. Cutting boards made from HDPE are a major source of microplastic shedding.

Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC, #3)

- Where you find it: plumbing pipes, vinyl flooring, credit cards, some cling films.

- Risks: often contains phthalates as plasticizers; heating or degradation releases toxic byproducts (dioxins, HCl).

Polypropylene (PP, #5)

- Where you find it: yogurt cups, baby bottles, reusable food containers, thermos lids, straws.

- Risks: considered safer than PVC, but still sheds microparticles with wear and heat. Common in baby bottles, though studies show particle release during preparation of formula.

Polystyrene (PS, #6)

- Where you find it: Styrofoam cups, clamshell takeout boxes, disposable cutlery.

- Risks: brittle, unstable with heat or acid; releases styrene (a possible carcinogen) and microplastics into food and drink.

Polycarbonate (PC, often #7 “Other”)

- Where you find it: older reusable water bottles, baby bottles (before BPA bans), eyeglass lenses, electronics.

- Risks: can leach bisphenol A (BPA); “BPA-free” often means BPS/BPF, which may not be safer.

Silicone (not a plastic, but often used as one)

- Where you find it: bakeware, baby bottle nipples, collapsible takeout containers.

- Risks: more heat-stable than plastics, but data on micro-shedding and long-term safety is limited.

The “Loh-down”

Plastics are ubiquitous because they’re cheap, light, and versatile. But their chemical backbone (fossil-derived hydrocarbons) and additives (phthalates, bisphenols, flame retardants) mean they’re not inert. Knowing the “big six” plastics helps you spot where exposure is coming from — and where swaps to glass, stainless, or natural materials may have the biggest payoff.

Plastic Pseudonyms

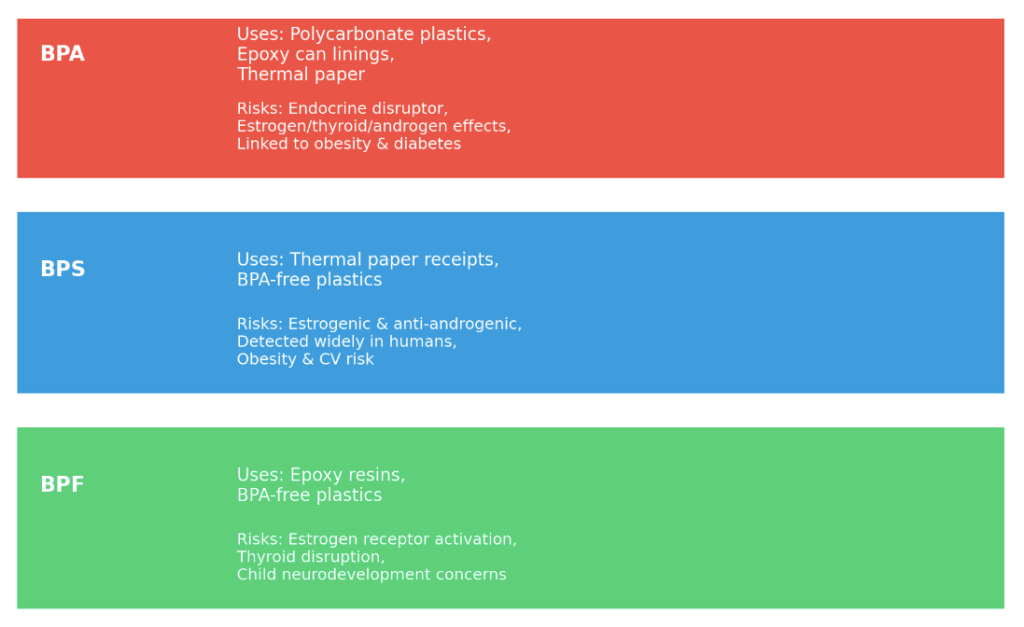

Beyond BPA: The Illusion of “BPA-Free”

“BPA-Free” is such a scam.

For years, bisphenol A (BPA) was the face of plastic toxicity. A key building block of polycarbonate plastics and epoxy resins, it leaches from food containers, can linings, and thermal receipts. BPA acts as an , binding to estrogen receptors and interfering with thyroid, androgen, and metabolic signaling.

When public concern grew, industry pivoted. Labels of “BPA-free” began appearing on bottles, baby products, and packaging. People began touting that their $96 water bottle was “BPA-free” and thus, “safe”. But what replaced BPA? Mostly chemical cousins: bisphenol S (BPS), bisphenol F (BPF), and other analogues. They were chosen not because they were proven safe, but because they had similar industrial properties.

The problem: “similar structure” often means “similar biology.”

- BPS — Now found widely in human urine samples worldwide, reflecting its heavy use in thermal paper receipts and BPA-free plastics. Studies show BPS has estrogenic and anti-androgenic activity, with potential links to obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk

- BPF — Used in epoxy resins and BPA-free plastics. Animal and cell studies show estrogen receptor activation and thyroid hormone disruption similar to BPA

- Other analogues (BPAF, BPZ, etc.) — Less common but detected in environmental and human samples; early evidence suggests many also mimic or block hormones

Emerging human data:

- NHANES data show BPS and BPF are now detected in a large majority of U.S. adults, often at levels comparable to BPA. Both are associated with obesity and insulin resistance markers.

- Prenatal BPF and BPS exposure has been linked to neurobehavioral changes in children, echoing concerns originally raised for BPA

The illusion of safety: “BPA-free” has become a marketing shield, but it doesn’t mean the product is biologically inert. Instead, we’ve created a game of chemical whack-a-mole, swapping one bisphenol for another with similar or even more potent endocrine activity.

BPA and its cousins

References

- Vandenberg LN, et al. Bisphenol-A and the great divide: a review of controversies in the field of endocrine disruption. Endocr Rev. 2009. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19819933/

- Rochester JR, Bolden AL. Bisphenol S and F: A systematic review and comparison to bisphenol A. Environ Health Perspect. 2015. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25775505/

- Yang Y, et al. Bisphenol analogues and endocrine-disrupting effects: a review. Chemosphere. 2019. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31035091/

- Pelch KE, et al. NTP Research Report on Bisphenol Analogues. Natl Toxicol Program. 2019. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31670920/

- Lehmler HJ, et al. Bisphenol S and F: Biomonitoring in the US and implications for human health. Environ Sci Technol. 2018. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29550154/

- Mustieles V, et al. Bisphenol A and analogues and child neurodevelopment outcomes. Environ Res. 2020. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32004885/

What happens when micro- and nanoplastics are in the brain? Read our Psyche section to find out.

What to do about Plastics? To receive your ACTION SUPPLEMENTS to this issue, leave your email here:

Explore more from Issue #1: The Microplastics in You

Pick the next section to read in Issue 1

Evidence Distilled. Action Amplified.