Issue 2: Beyond Keto: The Real Science of Insulin Resistance

Probe is where we test claims against physiology. Few topics need this more than “keto”. Between influencers, cookbook authors, and bro-science on social media, “keto” has become everything and nothing at once. Let’s strip it back to the medical definition, why most versions don’t qualify, and what happens when protein or fat are pushed too far.

Keto confusion on social media

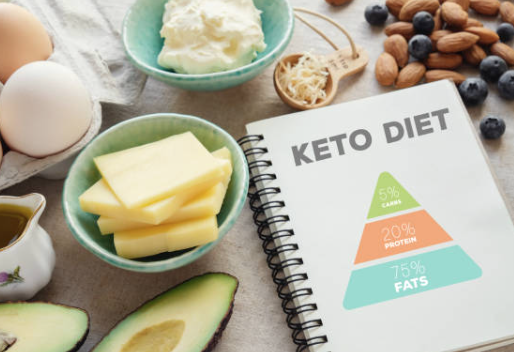

The Medical Ketogenic Diet — Ratios That Matter

When physicians and dietitians talk about a true ketogenic diet, they don’t mean “low carb.” They mean a diet with a carefully calculated ratio of fat to combined protein and carbohydrate:

- Classic 4:1 ketogenic diet

- 4 grams of fat for every 1 gram of protein + carbohydrate combined.

- ~90% of total calories from fat, 6% protein, 4% carbohydrate.

- The strictest version, typically used in pediatric epilepsy. Produces the deepest, most reliable ketosis.

- 3:1 ketogenic diet

- 3 grams of fat for every 1 gram of protein + carbohydrate.

- ~87% calories from fat, 10% protein, 3% carbohydrate.

- Less restrictive, sometimes used when patients can’t tolerate 4:1 but still need therapeutic ketone levels.

- 2:1 ketogenic diet

- 2 grams of fat for every 1 gram of protein + carbohydrate.

- ~82% calories from fat, 15% protein, 3% carbohydrate.

- Often used as a gentler therapeutic diet, sometimes in adults or as a transition from stricter ratios.

By comparison, most popular “keto” diets fall closer to 1:1 or less—sometimes 60–70% fat, 25–30% protein, and 5–10% carbohydrate. These macros may be “low carb,” but they often don’t predictably produce sustained blood ketone levels.

The point: a medical ketogenic diet is not casual or approximate. It’s carefully weighed, calculated, and monitored. Without those strict ratios, most so-called “keto” diets are really just low-carb, high-protein plans that rarely generate sustained therapeutic ketosis.

How Accurate Are Fingerstick Ketone Meters?

- What they measure: Fingerstick meters measure β-hydroxybutyrate (BHB), the main circulating ketone body. This is more accurate than urine strips (which measure acetoacetate and vary with hydration).

- Accuracy:

- Generally reliable for clinical and personal monitoring, but not perfect.

- Most devices are FDA-cleared for use in monitoring diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), where precision matters most.

- At nutritional levels of ketosis (0.5–5.0 mmol/L), they tend to slightly underestimate true blood BHB compared with laboratory assays.

- Variability can be ±0.2–0.4 mmol/L depending on the device.

- Limitations:

- More invasive and costly than urine strips (each strip can cost $1–2).

- Only reflect a single time point — ketone levels fluctuate throughout the day based on fasting, exercise, and meals.

- Not ideal for assessing long-term trends without context.

- Alternatives:

- Urine strips: Cheap, but less accurate and decline in reliability with long-term keto adaptation.

- Breath acetone analyzers: Noninvasive, variable accuracy, may better reflect fat oxidation than BHB directly.

Bottom line: Though not as precise as lab assays, fingerstick BHB meters are reliable enough for personal monitoring or diet adjustment.

Gluconeogenesis — The Detour Back to Sugar

A common misconception is that cutting out carbs means your body stops making glucose. Not so. The human body guards blood glucose like gold, because some tissues—the red blood cells, kidney medulla, the brain—can’t run on fat or ketones alone.

Enter gluconeogenesis: the liver’s ability to make new glucose from non-carbohydrate sources.

- Protein: Glucogenic amino acids like alanine and glutamine are readily converted into glucose. This is why “high-protein keto” is an oxymoron. Too much steak or whey protein? Your liver quietly turns it into sugar.

- Fat: Even fat can contribute. While long-chain fatty acids don’t enter the gluconeogenic pathway directly, the glycerol backbone of triglycerides does. Break down a triglyceride and you get three fatty acids (fuel) plus one glycerol (potential glucose). That glycerol can be recycled into sugar. Odd-chain fatty acids can enter the glucogenic cycle but in practice, this is not a significant substrate source.

- Other substrates: Lactate from exercising muscle also feeds into the cycle, ensuring glucose never truly runs out.

This is why the body can maintain blood glucose even during strict fasting or carbohydrate restriction. It’s also why many “keto” diets never achieve meaningful ketosis: too much protein or energy overall fuels gluconeogenesis, keeping glucose high enough to suppress ketone production.

The irony: gluconeogenesis is not your enemy—it’s survival. But it’s also proof that metabolism isn’t binary. You can cut carbs and still be making sugar. Which means a “keto” plate piled high with ribeye may be closer to low-carb-plus-gluconeogenesis than true ketosis.

Spotlight:The Heart’s Fuel of Choice

The healthy human heart is a metabolic omnivore, but it has a preferred fuel: fatty acids. In a normal adult at rest, 60–70% of cardiac ATP comes from fatty acid oxidation, with the remainder from glucose, lactate, and, under certain conditions, ketones .

Why fatty acids?

- They yield more ATP per molecule than glucose.

- The heart, contracting ceaselessly, thrives on this high-yield fuel.

- At the same time, the heart remains flexible—able to pivot toward glucose or lactate during exercise, stress, or hypoxia, when faster ATP turnover is required .

In disease, the story changes:

- Heart failure: The failing myocardium loses efficiency in fatty acid oxidation and turns increasingly to glucose and ketones. Ketones, in particular, provide an oxygen-efficient “rescue fuel” that may improve contractile function .

- Diabetes: Insulin resistance floods the heart with FFAs. The myocardium burns fat excessively, generating toxic intermediates (DAGs, ceramides) that impair contractility and mitochondrial function. Elevated baseline ketones are often seen as well, further complicating the metabolic profile .

The paradox of cardiac metabolism:

- The normal heart prefers fat.

- The failing heart leans on glucose and ketones.

- The diabetic heart is forced into fat overload, damaging itself with toxic byproducts.

This reshuffling underscores a larger truth: the “best” fuel isn’t fixed—it depends on the health of the organ and the state of the body.

Here’s a schematic of cardiac fuel preference:

- Healthy heart: mostly fatty acids, some glucose, minimal ketones.

- Failing heart: reduced fat use, more glucose and ketones.

- Diabetic heart: excessive fatty acid use, impaired glucose uptake, some ketones.

Ketone Therapy in Heart Failure — What the Trials Show (So Far)

HFpEF, 2-week oral ketone ester (crossover trial)

- Who was studied: People with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) — their hearts pump normally but the walls are stiff and don’t fill well.

- What was done: They took a ketone ester drink for 2 weeks, then switched to placebo in a crossover design.

- What happened: The ketone supplement made the heart pump more blood (↑ cardiac output), reduced the “back pressure” in the heart (↓ filling pressures), and made the heart muscle less stiff. During exercise, blood flow and pressure matched up more efficiently.

- Why it matters: For people with HFpEF, even small improvements in stiffness and filling can translate into easier breathing and more exercise tolerance.

HFrEF, acute β-hydroxybutyrate (3-OHB) infusion / ketone ester

- Who was studied: People with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) — their hearts have weakened pumping function.

- What was done: They were given an IV infusion of the ketone body β-hydroxybutyrate (3-OHB), or in some cases an oral ketone ester, in small controlled trials.

- What happened: Within hours, their hearts pumped more effectively (↑ cardiac output, ↑ ejection fraction) and blood pressure in the lungs dropped (decongestion).

- Why it matters: These short-term boosts suggest ketones can act as a quick, efficient fuel source for failing hearts, especially when standard fuels (fat, glucose) aren’t working well.

Ongoing and related trials (KETO-HFpEF and others)

- What’s happening: Larger, longer studies are testing whether ketones can consistently improve symptoms, exercise tolerance, and outcomes in both HFpEF and HFrEF. Reviews suggest ketones are “oxygen-efficient fuel” — meaning they help the heart do more work with less oxygen demand.

What reviewers conclude

Small, mostly short-duration RCTs/series show consistent acute hemodynamic gains (↑ CO/LVEF; ↓ PCWP) with exogenous ketones in HF. The failing myocardium up-regulates ketone use, and supplying ketones may act as an oxygen-efficient “rescue” substrate. Larger, longer outcomes trials are still needed before routine clinical adoption.

Caveats:

- Trials are small, short, with heterogeneous populations (HFpEF vs HFrEF; ± T2D).

- Dosing routes differ (IV 3-OHB vs oral ketone esters), making comparisons tricky.

- Not a substitute for guideline-directed therapy; think of ketones as a metabolic adjunct pending larger RCTs.

How SGLT2 Inhibitors Increase Ketones (Why These Drugs Look “Metabolic”)

SGLT2 inhibitors lower blood glucose by making you excrete glucose through urine.

That glucose loss mimics a mild fasting signal inside the body: insulin levels fall, glucagon rises, and adipose tissue releases more free fatty acids. The liver responds the same way it does during early nutritional ketosis—by increasing β-oxidation and diverting excess acetyl-CoA into ketone production.

Importantly, this is regulated, low-level ketogenesis. SGLT2 inhibitors shift the internal hormonal ratio (↓ insulin, ↑ glucagon) just enough to push metabolism toward fat oxidation and small rises in β-hydroxybutyrate—a shift many researchers believe contributes to their unexpected benefits in heart failure and kidney disease.

This subtle metabolic shift is why HFpEF and HFrEF trials increasingly view ketones as alternative fuel—one reason SGLT2 inhibitors may appear to ‘improve cardiac efficiency.

SGLT2 Inhibitor Trials

DAPA-HF (dapagliflozin, reduced ejection fraction)

- Who was studied: People with weakened pumping function of the heart (HFrEF), with or without diabetes.

- What happened: Patients taking dapagliflozin were less likely to die of heart problems and less likely to end up in the hospital for worsening heart failure compared to those on placebo.

- Key point: The drug helped people whether or not they had diabetes, showing it’s not just a “diabetes drug.”

EMPEROR-Reduced (empagliflozin, reduced ejection fraction)

- Who was studied: Similar group—people with HFrEF, with and without diabetes.

- What happened: Empagliflozin cut the risk of heart failure hospitalizations by about 25% and improved quality of life. Benefits appeared within weeks.

- Key point: Empagliflozin consistently helped keep people out of the hospital.

DELIVER (dapagliflozin, mildly reduced and preserved ejection fraction)

- Who was studied: People whose hearts pumped better (HFpEF and HFmrEF), where few treatments had worked before.

- What happened: Dapagliflozin reduced the risk of worsening heart failure or death from cardiovascular causes, across the full range of patients with EF >40%.

- Key point: This trial showed the benefits of SGLT2 inhibitors extend beyond “weak hearts” to people with stiffer, but still pumping hearts.

SOLOIST-WHF (sotagliflozin, after worsening heart failure)

What happened: Starting sotagliflozin soon after discharge reduced repeat hospitalizations and deaths from cardiovascular causes.

Who was studied: People with type 2 diabetes who had just been hospitalized for worsening heart failure.

Key point: Even very sick patients benefited, and the improvements were seen quickly.

Takeaway

These trials together tell a consistent story: SGLT2 inhibitors make hearts more resilient. They keep people out of the hospital, help them live longer, and work across the spectrum of heart failure — even in people without diabetes.

Ketones in the ICU — Hype or Hope?

- Animal studies:

- In rodent models of sepsis and endotoxemia, ketone supplementation (either ketone esters or β-hydroxybutyrate infusion) has been shown to reduce systemic inflammation, improve mitochondrial function, and improve survival in some settings. Proposed mechanisms include inhibition of the NLRP3 inflammasome, stabilization of redox balance, and improved energy efficiency under metabolic stress.

- Example: Exogenous ketones improved survival and attenuated cytokine storm in lipopolysaccharide-induced sepsis models.

- Human evidence:

- As of now, no large randomized controlled trials have tested exogenous ketones in septic ICU patients.

- A few early-phase pilot studies in critically ill patients (not always sepsis-specific) suggest ketones are safe to administer intravenously, but clinical outcome data (mortality, organ failure, length of stay) are lacking.

- Reviews in Critical Care and Frontiers in Immunology note ketones as a “promising metabolic therapy” in critical illness but emphasize that translation from bench to bedside has not yet occurred.

- Key barrier: ICU patients with sepsis have highly variable metabolic states (insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, elevated endogenous ketones). Giving exogenous ketones may not be uniformly beneficial, and dosing/timing remain open questions.

Bottom line:

In theory, ketones could help septic patients by calming runaway inflammation and supplying efficient energy when mitochondria are stressed. In practice, this remains speculative: the data are preclinical or very early-phase.

Spotlight: Lungs, Kidneys, Liver

Lungs

What looks promising (mostly preclinical/early translational):

- Anti-inflammatory signaling: β-hydroxybutyrate (BHB) inhibits the NLRP3 inflammasome, a pathway implicated across airway diseases (asthma, COPD). That’s robust bench science and widely replicated.

- Acute lung injury/ARDS models: In sepsis-associated acute lung injury, exogenous BHB reduced inflammation and injury in animal models. Reviews of critical illness suggest ketones may act as an alternative substrate and modulate immune function (including T-cell “reprogramming”) in ARDS—but this is not yet established therapy.

- Asthma (early): New work suggests BHB can relax bronchial smooth muscle and dampen inflammation in experimental asthma models. Human efficacy is not yet known.

Bottom line: strong mechanistic rationale, encouraging animal/physiology data; no large human trials showing outcome benefits in COPD/asthma/ARDS yet. Good hypothesis, not a clinical recommendation.

Kidneys

Signals of benefit (with caveats):

- CKD safety & metabolic effects: Contemporary reviews argue that ketogenic metabolic therapy (KD or closely related interventions) can be safe in stage 2–3 CKD under supervision and may improve glycemia and weight—key drivers of renal decline. This remains debated and must be individualized.

- Diabetic kidney disease (DKD): Reviews point to BHB’s potential to slow DKD progression via improved substrate handling, autophagy, and anti-inflammatory effects; human outcomes data are still limited.

- ADPKD: Observational/associative work suggests higher endogenous BHB correlates with slower disease progression; animal models of PKD show benefit with ketogenic states. Human interventional trials are ongoing.

Cautions:

- Protein load, volume status, electrolytes, and acid–base balance matter in CKD; any ketogenic strategy should be clinically supervised. Evidence is growing but not definitive.

Bottom line: plausible renoprotective biology + early human signals; promising but not settled. Use case-by-case, especially in CKD.

Liver disease / Cirrhosis

NAFLD/MASLD (earlier disease):

- Impaired hepatic ketogenesis shows up in human NAFLD and relates to worse metabolic flux (more TCA cycling, gluconeogenesis), while restoring/maintaining ketogenesis appears protective in models and small human studies. Short-term ketogenic interventions have reversed hepatic steatosis and improved hepatic insulin sensitivity/redox state.

- Emerging work argues ketogenesis itself (not just fat oxidation) mitigates MASLD progression.

Advanced disease / cirrhosis:

- As fatty liver advances toward cirrhosis/HCC, hepatic expression of HMGCS2 (the rate-limiting ketogenic enzyme) is suppressed, implying blunted ketogenesis in advanced disease. That’s been observed in human tissue studies and reviews.

- Clinical data specifically testing ketogenic diets or exogenous ketones in cirrhosis are sparse. Given malnutrition risk, sarcopenia, and ammonia handling in decompensated disease, any ketone-raising approach should be cautious and supervised; this is not a plug-and-play therapy.

Bottom line: in MASLD/NAFLD, maintaining ketogenesis looks metabolically protective; in established cirrhosis, hepatic ketone production is often impaired and clinical trials are lacking—so no blanket recommendations.

In sum:

Lungs: Ketones/BHB hit relevant inflammatory switches (NLRP3) and may aid immune function under stress, but we need proper human trials before claiming benefit in COPD/asthma/ARDS.

Kidneys: Metabolic improvements and anti-inflammatory effects make sense biologically; early human evidence supports safety in mild-to-moderate CKD with supervision, and ADPKD signals are intriguing. Individualize with medical care.

Cirrhosis: We can’t conflate NAFLD improvements with cirrhosis management. As disease advances, ketogenesis is downregulated; the clinical role of ketogenic strategies here remains uncertain.

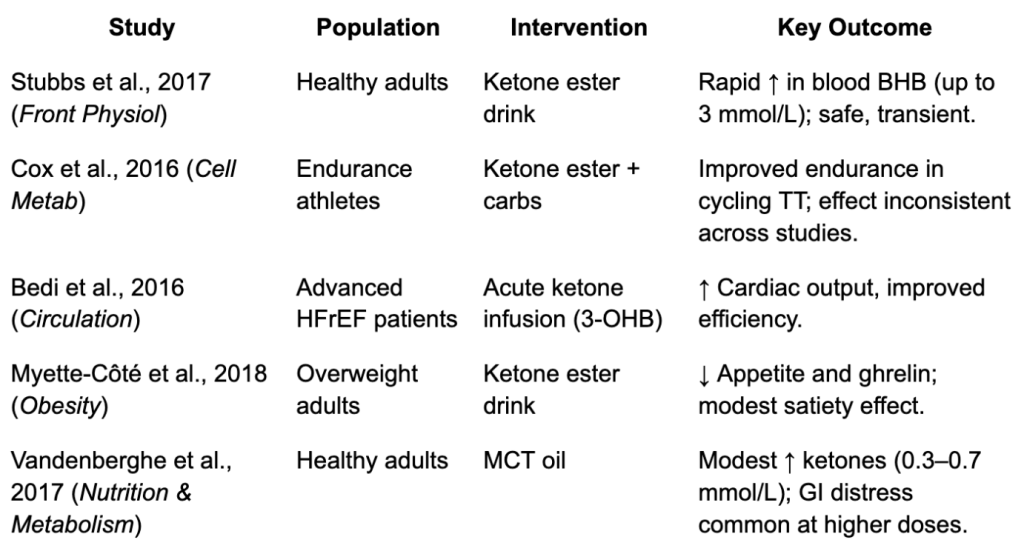

Exogenous Ketones — Can You Drink Your Way Into Ketosis?

The promise of exogenous ketones is seductive: instead of fasting or following a strict ketogenic diet, you just swallow a supplement and raise your ketone levels. Blood ketones rise within minutes, giving you the biochemical profile of “ketosis” without the diet.

But what does that really mean?

- Yes, blood ketones rise. You can hit 1–3 mmol/L after a drink.

- No, it’s not the same as nutritional ketosis. You don’t shift your metabolism; you’ve just added ketones from the outside. Glucose may still be high, insulin still elevated, and fatty acid flux unchanged.

- Short-lived: Ketone levels peak for 1–3 hours, then drop back down unless you keep re-dosing.

Some small studies suggest exogenous ketones can:

- Improve short-term endurance performance in athletes.

- Temporarily boost cardiac output in failing hearts.

- Suppress appetite in some individuals.

But the evidence is inconsistent, the effects are modest, and many claims outpace the science.

Types of Exogenous Ketones

There are three main categories, each with pros and cons:

- Ketone Salts

- What they are: β-hydroxybutyrate (BHB) bound to minerals like sodium, potassium, calcium, or magnesium.

- Pros: Widely available, cheaper.

- Cons: Require large doses; can cause GI distress; the mineral load (especially sodium) can be problematic. Typically raise ketones to 0.5–1.0 mmol/L.

- Ketone Esters

- What they are: BHB or acetoacetate linked to an alcohol backbone (e.g., (R)-3-hydroxybutyl (R)-3-hydroxybutyrate, often called “ΔG”).

- Pros: Potent, can raise ketones to 2–3 mmol/L rapidly.

- Cons: Expensive, taste notoriously unpleasant, limited availability. Mostly used in research or by elite athletes.

- Medium-Chain Triglycerides (MCTs)

- What they are: Fats (like caprylic acid, C8) that are rapidly absorbed and transported to the liver, where they’re converted into ketones.

- Pros: Easy to buy, relatively inexpensive, moderate ketone boost.

- Cons: GI upset at higher doses; less potent (typical rise 0.3–0.7 mmol/L).

The bottom line: Exogenous ketones do raise blood ketone levels, but only for a short window, and without reproducing the full physiologic state of nutritional ketosis. They may prove useful in research or niche medical settings, but for most consumers, the benefits are short-lived and still speculative.

What Happens to Excess Ketones?

Ketones are water-soluble molecules (unlike fatty acids). That changes how the body handles them.

- Immediate use, if possible

- Heart, brain, and muscle will burn ketones quickly when they’re available. They enter mitochondria directly and don’t require insulin.

- If supply exceeds demand

- The liver doesn’t “store” ketones — it makes them continuously from fatty acids and releases them into the blood.

- Extra ketones circulating in the blood will:

- Be excreted in urine (ketonuria).

- Be exhaled as acetone (on the breath).

- Be metabolized back into acetyl-CoA and ultimately converted into fatty acids or cholesterol if energy remains in surplus.

- Translation for excess energy intake

- With excess energy intake vs. expenditure, adding ketones on top results in the excess carbon and energy eventually getting stored as fat.

- The unique feature is that ketones are not packaged into triglycerides the way carbs and fats are. Instead, they’re either burned or excreted. But with excess energy intake vs. expenditure, your tissues use ketones as fuel, and simultaneously spare the oxidation of glucose and fatty acids coming in from your diet. Those spared nutrients now become the “excess” that shifts into storage. In other words, high ketone availability reduces the need to burn other fuels; the unburned carbs and fats are what ultimately get converted to triglycerides and stored in adipose tissue.

Actionable Insights on Ketones & Insulin Resistance

1. Most “keto” diets aren’t keto.

- True ketogenic diets (4:1, 3:1 ratios) are medical therapies, not lifestyle trends.

- Popular “low-carb, high-protein” plans often fuel gluconeogenesis instead, keeping people out of ketosis.

- Action: If you’re “doing keto” but never measure blood ketones, you’re probably doing low-carb. Be honest about the difference.

2. Protein balance matters.

- Excess protein is converted to glucose (gluconeogenesis), blunting ketone production.

- Action: Low-carb ≠ unlimited protein. Ketosis requires moderating protein as well as carbs.

3. The failing heart and sick brain may benefit from ketones — but not through supplements yet.

- Clinical studies suggest ketones improve cardiac output in heart failure and support brain function in MCI/early dementia.

- But effects are short-term, small trials, and not ready for broad use.

- Action: Patients should not self-prescribe exogenous ketones for heart failure or dementia. These remain experimental therapies under study.

4. Exogenous ketones ≠ nutritional ketosis.

- Ketone esters, salts, and MCTs can raise blood ketones for a few hours but don’t recreate the physiology of a ketogenic diet.

- Action: If you’re considering supplements, know what they do: short-lived, expensive, and often overhyped.

5. Ketones and organ disease — interesting, not yet practical.

Action: These are frontier science areas. Not actionable now, but worth watching as trials develop.

Lungs (COPD/asthma/ARDS): Anti-inflammatory signals look promising, but no human outcome data.

Kidneys: Ketogenic states may help in earlier CKD/ADPKD under medical supervision, but evidence is still thin.

Liver: Ketogenesis protects in NAFLD, but in cirrhosis ketone production falls; no clinical trials yet.

6. The safest, evidence-based path to metabolic flexibility remains…

- Dietary pattern: Whole-food, low processed-carbohydrate eating that reduces insulin resistance.

- Exercise: Regular activity increases glucose uptake independent of insulin and improves metabolic flexibility.

- Action: Instead of chasing “deep keto,” focus on metabolic health fundamentals — weight management, resistance training, sleep, and stress reduction. These consistently improve insulin sensitivity.

References

- Kossoff EH, et al. “Optimal clinical uses of ketogenic diets.” Epilepsia. 2009.

- Masood W, et al. “Ketogenic Diet.” StatPearls. 2023.

- 3. Bisschop PH, et al. “Gluconeogenesis during fasting in humans.” J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000.

- Lopaschuk GD, et al. Myocardial fatty acid metabolism in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2010;90(1):207–258.

- Stanley WC, et al. Myocardial substrate metabolism in the normal and failing heart. Physiol Rev. 2005;85(3):1093–1129.

- Bedi KC, et al. Evidence for intramyocardial disruption of lipid metabolism and increased myocardial ketone utilization in advanced human heart failure. Circulation. 2016;133(8):706–716.

- Yurista SR, et al. Ketone metabolism as a therapeutic target for heart failure. Circulation. 2021;144(22):1876–1888.

- Fillmore N, et al. Metabolic remodeling in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Res. 2014;104(3):423–436.

- Nielsen R, et al. Cardiac ketone body metabolism in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(22):2901–2910.

- Nielsen R, et al. “Ketone ester increases cardiac output in HFpEF: randomized crossover trial.” Circulation. 2019.

- Horton JL, et al. “Increased ketosis as alternative fuel in heart failure.” Circulation. 2019.

6. Yurista SR, et al. “Ketone therapy in heart failure.” J Am Coll Cardiol HF. 2021. - Cox PJ, et al. “Ketone ester drinks: metabolic effects.” Cell Metab. 2016.

- Stubbs BJ, et al. “Exogenous ketones: physiology, types, and therapeutic potential.” Front Physiol. 2017.

- Clarke K, et al. “Safety of ketone ester drinks in humans.” Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2012.

- Friedman AN, et al. “Ketogenic diet use in CKD: review.” Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2020.

- Torres VE, et al. “Ketogenic metabolic therapy in ADPKD.” J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019.

- Perry RJ, et al. “Hepatic redox & NAFLD.” Cell Metab. 2020.

- Carlson MG, et al. “Impaired ketogenesis in NAFLD.” Hepatology.

- García-Ruiz C, et al. “Mitochondria & impaired ketogenesis in cirrhosis.” Hepatology. 2013.

Want to know about Money in Metabolism? Check out Prosper next.

Explore more from Issue #2: Beyond Keto: The Real Science of Insulin Resistance

Pick the next section to read in Issue 1