Eating for Insulin Sensitivity: Mechanisms, Trade-offs, and Reality

This is about reducing unnecessary insulin demand while preserving metabolic flexibility. Homo sapiens survived because of its ability to adapt to changing environments and contexts. This flexibility is a hallmark strength of the species. We should flex it for optimal human performance. The true Paleo was the ability to switch fuels to match the occasion.

***Obviously, if you’re on medications, you should be managing them with your doctor.

1. Insulin Sensitivity Is About Demand, Not Suppression

Insulin resistance develops when insulin is required:

- too frequently

- in excessive amounts

- across too many competing pathways

The goal is not low insulin.

The goal is appropriate insulin for the task at hand.

Lock in Eating Structure First (Non-Negotiable)

Action:

- Choose 3, 4, or 5 eating episodes per day (4-5 preferred)

- Space them ≥3 hours apart

- Keep timing consistent day to day

Rules:

- No eating outside scheduled times

- No “just a bite”

- No exceptions for liquids with calories

If this isn’t in place, nothing else matters.

2. Why Meal Structure Matters

Eating continuously keeps insulin elevated even if:

- meals are “healthy”

- carbohydrates are modest

- calories are controlled

Structured meals work because they:

- create insulin peaks and valleys

- allow adipose lipolysis between meals

- reduce hepatic glucose output dysregulation

This is why grazing undermines insulin sensitivity even on “clean” diets.

Snacks: What People Are Really Asking For

Usually, when I am working with a patient and we’ve scheduled our meals, the most common question I get is: What about snacks, Dr. Loh?

At first, this puzzled me. We had just scheduled FIVE meals per day together. Why was this person now asking me about snacks?

There is an American obsession with snacks and over time, I realized that what my patients are really asking for is PERMISSION. They are usually concerned about one of three things:

- “Am I allowed to eat between meals?”

- “Can I have something sweet or comforting?”

- “I’m afraid of being hungry.”

None of these is solved by snack lists.

Why the Word “Snack” Is the Problem

In practice, “snacks” almost always mean:

- refined carbohydrates

- sweet foods

- ultra-processed convenience items

They are rarely:

- protein-forward

- nutritionally complete

- metabolically neutral

So when patients ask about snacks, what they are often seeking is permission to keep insulin elevated between meals.

From a metabolic standpoint, that undermines the goal.

How I Frame It Clinically: Meals Are Dosed

Rather than “meals vs snacks,” I use dosing language.

- Food is a metabolic signal

- Insulin is the response

- Timing matters

This is why I often prescribe:

- 4–5 meals per day

- at least 3 hours apart

- every eating episode contains protein

At that point, physiologically speaking, there is no metabolic need for snacks.

If hunger is present, it means:

- the previous meal was under-dosed (often protein)

- or insulin never came down

- or sleep/stress is interfering

The solution is to fix the meal (or other problem), not add a snack.

A Useful Reframe

Instead of asking can I have a snack? try asking do I need another meal, or was my last one insufficient?

If the answer is “I need food,” then:

- eat protein

- eat a real meal

- eat it intentionally

If the answer is “I want something,” that’s a different conversation.

What About Kids?

This question often comes wrapped in concern for children–>”I bought the peanut butter for the kids because they need snacks…“

Un-huh:

- Most children around the world do not have scheduled snack times

- They eat meals

- They play

- They are metabolically fine

Constant snacking is a cultural habit, not a biological requirement.

For kids, frequent sweet snacks:

- train constant insulin release

- disrupt hunger cues

- normalize grazing behavior early

That doesn’t mean children should be hungry —it means they should eat real meals.

Most snack questions are not about hunger. They are about habit, comfort, or permission.If you’re eating protein-containing meals every 3-4 hours and still feel the need to snack, the issue is not discipline. It’s dosing, timing, or physiology.

3. Protein Is an Insulin Modulator, Not Just a Macronutrient

Protein:

- stimulates insulin modestly

- suppresses glucagon-driven glucose release

- stabilizes post-meal glucose curves

Importantly:

- protein-driven insulin release is contextual, not pathological

- inadequate protein worsens insulin resistance by promoting:

- muscle loss

- reactive hunger

- compensatory overeating

Protein Is Mandatory at Every Eating Episode

Action:

- Adults: 25–30 g protein per eating episode

- Children: size-appropriate protein at every meal

If you are unwilling to eat protein:

- do not eat

- you are not hungry. You are seeking stimulation or comfort. Eating will only make you feel better temporarily. When you finish, you’ll still be looking for stimulation and/or comfort.

4. Carbohydrates Are a Load — Context Determines Cost

Carbohydrates:

- require insulin for disposal

- compete with fat for oxidation

- increase hepatic glucose flux

They are best tolerated when:

- muscle glycogen is depleted

- paired with protein and fat

- insulin sensitivity is higher (earlier in the day, post-exercise)

They are least tolerated when:

- eaten alone

- stacked across meals

- consumed late at night

This is why placement matters more than complete elimination.

Carbohydrates Are Assigned, Not Automatic

Action:

- Choose which meals include carbohydrates

- Default: one carb-containing meal per day

- Add a second only if:

- training volume is high

- CGM shows rapid recovery

- hunger and energy are stable

Rules:

- Never eat carbohydrates alone

- Never stack carbs at multiple meals “just because”

Carbs are a load. You assign where they go.

5.“Too Much Protein” Can Still Raise Glucose

Excess protein:

- increases gluconeogenic substrate availability

- raises glucagon

- can increase hepatic glucose output in insulin-resistant states

This is not a reason to fear protein — it’s a reason to:

- avoid turning protein into a replacement carb

- distribute intake across meals

- avoid very high protein with minimal energy expenditure

Gluconeogenesis is demand-driven, but substrate matters when regulation is impaired.

Action:

- Do not use very high protein intake to replace carbohydrates indefinitely

- Distribute protein evenly across meals

- Avoid turning protein into a constant gluconeogenic substrate stream

If glucose rises disproportionately after high-protein meals:

- reduce protein dose per meal

- improve insulin sensitivity elsewhere (get your zzzz’s, for example!!!)

- increase movement, not restriction

6. Fat: Insulin-Neutral Does Not Mean Metabolically Neutral

Dietary fat:

- does not spike glucose

- does not require insulin for uptake

But:

- it still delivers energy

- excess fat can worsen hepatic insulin resistance

- high fat intake can slow glucose clearance when stacked with carbs

This explains why:

- “keto” diets can worsen insulin resistance in some individuals

- fat + carb combinations are especially metabolically costly

Fat is not the villain but it is not invisible. Like all foods, it has a metabolic cost.

Action:

- Use fat to support satiety, not to force ketosis

- Avoid combining large fat loads with large carb loads

- Do not “add fat” to already adequate meals

If fasting triglycerides rise or CGM recovery slows:

- reduce total fat load

- reassess liver insulin resistance

7. Why Walking After Meals Works (Even If You’re Fit)

After a meal, glucose can be cleared from the bloodstream through two main pathways:

- Insulin-mediated uptake (what most people rely on)

- Contraction-mediated uptake (which bypasses insulin)

Movement activates the second pathway.

Muscle contraction:

- stimulates GLUT4 translocation independent of insulin

- increases glucose uptake without raising insulin levels

- shortens post-meal glucose exposure

This effect:

- occurs with light activity (such as walking)

- does not require sweat or intensity

- works even in insulin resistance

The Soleus Muscle: A Special Case

The soleus is a deep calf muscle that:

- is highly oxidative

- is active during standing and low-level movement

- can sustain prolonged contraction without fatigue

Unlike many muscles, the soleus:

- preferentially uses blood glucose and triglycerides

- can remain metabolically active for long periods

- meaningfully contributes to glucose disposal even at low workloads

The Soleus Pump

The soleus pump refers to:

- repeated heel raises or seated plantar flexion

- performed slowly and rhythmically

- often while sitting or standing in place

This activates the soleus muscle continuously, creating a local glucose sink.

Research suggests:

- soleus activation can significantly lower post-meal glucose

- effects may approach or complement light walking

- especially useful for people who are sedentary, injured, or desk-bound

Option A: Walking (Preferred)

Action:

- Walk 5–10 minutes after carb-containing meals

- Easy pace is sufficient

Option B: Soleus Pump (Valid Alternative)

Action:

- Perform seated or standing heel raises

- Knees slightly bent

- Slow, rhythmic tempo

- 5–15 minutes

Use the soleus pump when:

- walking isn’t possible

- you are chair- or bed-bound

- you are desk-bound

Bottom line:

Walking is still superior** for whole-body metabolic health but the soleus pump is a legitimate alternative, not a gimmick.

- If you can walk after meals → do that

- If you can’t → activate the soleus for 5–15 minutes

- If you’re desk-bound → alternate soleus pumping with standing

The goal is not exercise. The goal is post-meal glucose disposal without additional insulin demand.

**Walking uses many muscles; the soleus pump uses one exceptionally efficient one.

How to do The Soleus Pump

Option A: Seated Soleus Pump (Most Accessible)

Best for:

- chair-bound patients

- desk workers

- anyone after meals or during long sitting periods

How to do it:

- Sit with feet flat on the floor

- Keep the front of the foot down

- Slowly lift the heels as high as comfortable

- Lower heels slowly back to the floor

Tempo:

- Lift: 2 seconds

- Lower: 2–3 seconds

Duration:

- 5–15 minutes after meals

- Can be broken into shorter sets

Key cue:

You should feel this low in the calf, not in the thigh.

Option B: Standing Soleus Pump

Best for:

- people who can stand but don’t want to walk

- quick post-meal movement

How to do it:

- Stand holding a chair or wall for balance

- Keep knees slightly bent (this biases the soleus vs. gastrocnemius)

- Slowly raise heels

- Lower with control

Same tempo and duration as seated version

Option C: Bed-Based Soleus Activation

Best for:

- bed-bound patients

- recovery days

- limited mobility

How to do it:

- Lie on your back or sit upright in bed

- Gently point toes away (plantar flexion)

- Slowly return to neutral

This is lower intensity but still activates the soleus.

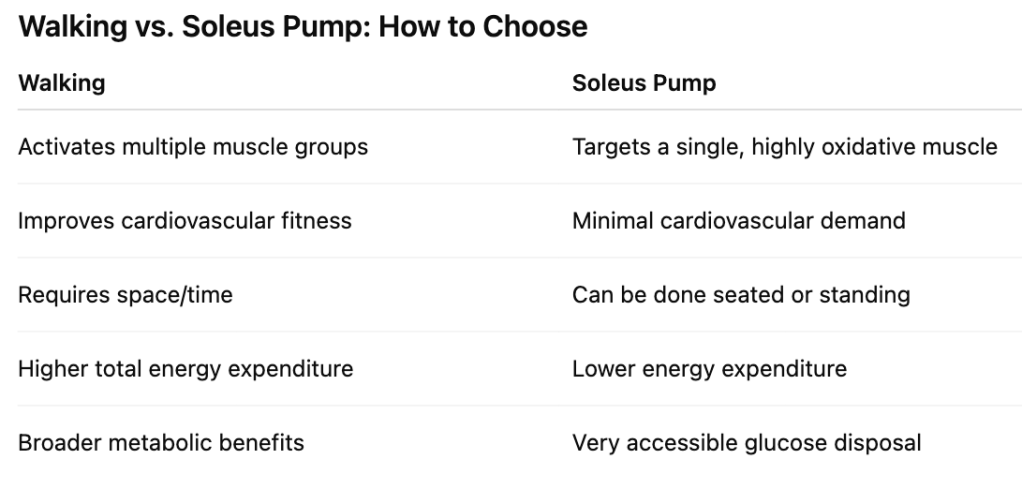

How This Compares to Walking

- Walking uses many muscles → broader metabolic benefits

- Soleus pumping uses one exceptionally efficient muscle → targeted glucose clearance

Walking is preferred when possible.

The soleus pump is a valid substitute when it’s not.

When to Use It

- After carbohydrate-containing meals

- During prolonged sitting (long commutes, air travel)

- On days when walking isn’t feasible

- As a supplement, not a replacement, for general movement

What It Should (and Should Not) Feel Like

Normal:

- mild calf fatigue

- warmth in lower legs

Not expected:

- sharp pain

- cramping

- joint discomfort

If pain occurs → stop and reassess positioning.

The soleus pump is a low-intensity, insulin-independent way to help clear post-meal glucose — especially useful when walking isn’t an option.

8. Stop eating 3 hours before bed

Eating and sleeping are diametrically opposed. Stopping your feeding window before bedtime signals your body to prepare for sleep.

Action:

- Stop eating ≥3 hours before bedtime

- Kitchen is closed — no exceptions

Late eating worsens:

- nocturnal insulin levels

- sleep quality

- next-day glucose tolerance

9. Sleep Is a Glucose Regulator, Not a Lifestyle Add-On

Sleep restriction:

- raises cortisol

- increases hepatic glucose output

- worsens next-day insulin sensitivity

Irregular sleep timing:

- disrupts circadian insulin signaling

- impairs beta-cell responsiveness

This is why:

- fixed sleep schedules matter more than “sleep hacks”

- late-night eating worsens glucose tolerance

Sleep Is Scheduled Like Medication

Action:

- Fixed bedtime and wake time (±30 minutes)

- 7–8 hours in bed

- No “catch-up” sleep

If sleep is poor:

- expect worse glucose control

- do not compensate with food

10. Alcohol: Optional, Never Neutral

Alcohol:

- acutely suppresses hepatic gluconeogenesis

- later worsens insulin sensitivity

- increases triglycerides and sleep fragmentation

From a metabolic perspective:

- zero alcohol is optimal

- any intake is a trade-off, not a free variable

Action:

- For metabolic optimization: no alcohol

- If choosing to drink:

- do not drink daily

- do not drink late

- expect impaired glucose control

Your choice. Also, your health outcomes.

11. CGMs: How to Use the Data Without Becoming Neurotic

CGMs are best used to:

- compare meals

- observe trends across days

- identify repeated stress patterns

They should not be used to:

- chase flat lines

- judge single spikes

- micromanage eating

Focus on:

- height of excursions

- duration above baseline

- recovery time

CGM Is Used as an Audit Tool, Not a Control Device

Action:

- Review CGM data once daily

- Focus on:

- spike height

- duration above baseline

- recovery time

Ignore:

- single numbers

- perfection

- comparison to others

Use CGM data to:

- remove foods

- reassign carbs

- add movement

Not to micromanage eating.

12. The Real Endpoint: Metabolic Flexibility

Success looks like:

- stable energy between meals

- predictable hunger

- glucose that rises and returns

- ability to tolerate a range of foods without chaos

That’s not discipline.

That’s physiology working.

Why You Don’t Need “Keto”

Ketosis can:

- lower insulin

- reduce glucose variability

- provide therapeutic benefits in select contexts

But:

- it is not required for insulin sensitivity

- it does not correct all metabolic dysfunction

- it can mask underlying rigidity if misused

Flexibility is key for long-term metabolic health.

Keep in Mind:

- Don’t kid yourself–metabolic flexibility doesn’t mean bending the rules of good nutrition. It means not having a rigid plan that can fall apart once your context changes (work schedule, travel, etc.)

- Track what you’re doing. (Feeling like you followed the plan is not the same as actually following the plan!)

- It’s okay to make mistakes–you can always get better. It’s not good to lie to yourself–there’s no recovery from that.

References

Jenkins DJA, et al. Effect of meal frequency on glucose and insulin metabolism. Am J Clin Nutr. 1989;49(5):861–867.

Kahleova H, et al. Eating two larger meals a day improves insulin sensitivity compared with six smaller meals. Diabetologia. 2014;57(8):1552–1560.

Stote KS, et al. A controlled trial of reduced meal frequency without caloric restriction. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85(4):981–988.

Wolfe RR. The underappreciated role of muscle in health and disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84(3):475–482.

Layman DK, et al. Protein quantity and quality at meals influence insulin sensitivity. J Nutr. 2009;139(3):525–531.

Petersen KF, et al. Skeletal muscle insulin resistance and lipid accumulation. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(7):664–671.

Monnier L, et al. Contributions of fasting and postprandial glucose to HbA1c. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(3):881–885.

Cavalot F, et al. Postprandial blood glucose predicts cardiovascular events. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(3):523–528.

Blaak EE, et al. Glucose metabolism and timing of carbohydrate intake. Proc Nutr Soc. 2019;78(1):12–20.

Samuel VT, Shulman GI. Mechanisms for insulin resistance: common threads. Cell. 2012;148(5):852–871.

Fabbrini E, et al. Increased liver fat causes hepatic insulin resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(37):15430–15435.

Sparks JD, et al. Dietary fat and hepatic VLDL secretion. J Lipid Res. 2012;53(6):1101–1113.

Mattson MP, et al. Meal frequency and timing in health and disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(47):16647–16653.

Holmstrup ME, et al. Frequent snacking increases insulin exposure without benefit. J Nutr. 2010;140(3):552–557.

Colberg SR, et al. Physical activity/exercise and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(11):2065–2079.

Richter EA, Hargreaves M. Exercise, GLUT4, and skeletal muscle glucose uptake. Physiol Rev. 2013;93(3):993–1017.

Hamilton MT, et al. Role of low-level muscle activity in metabolic health. Diabetes. 2007;56(11):2655–2667.

Hamilton MT, et al. Prolonged sitting and muscle inactivity physiology. Compr Physiol. 2018;8(4):1771–1790.

Hamilton MT, et al. Soleus muscle contractions improve glucose regulation. iScience. 2022;25(1):103988.

Spiegel K, et al. Sleep loss causes insulin resistance. Lancet. 1999;354(9188):1435–1439.

Buxton OM, et al. Circadian misalignment increases metabolic risk. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(129):129ra43.

Depner CM, et al. Mistimed sleep disrupts glucose tolerance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104(8):3561–3570.

Steiner JL, Lang CH. Alcohol, insulin resistance, and metabolism. Alcohol Res. 2017;38(2):249–259.

Siler SQ, et al. Alcohol and hepatic glucose production. J Clin Invest. 1998;101(12):2625–2633.

Heinemann L. Continuous glucose monitoring and interstitial glucose. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2010;4(4):952–960.

Basu A, et al. Interstitial glucose lag and CGM interpretation. Diabetes. 2013;62(3):840–847.

Rodbard D. Interpretation of continuous glucose monitoring data. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2016;18(S2):S3–S12.

Ferrannini E, et al. Insulin resistance and metabolic flexibility. Diabetologia. 2015;58(3):457–466.

Kelley DE, Mandarino LJ. Fuel selection and insulin resistance. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72(3):697–703.

Do what you can. Default to the Life is Short List (a.k.a. LISL) whenever this list feels like it’s too much. Or, use the OCD list most of the time and switch to the LISL for specific periods/events (e.g . when travelling).