Issue 3: New Insights into Muscle Health

Let’s dive inside Muscle and discover its role in immunity, recovery and the Fat-Muscle-Bone axis.

Muscle as an Immune Organ

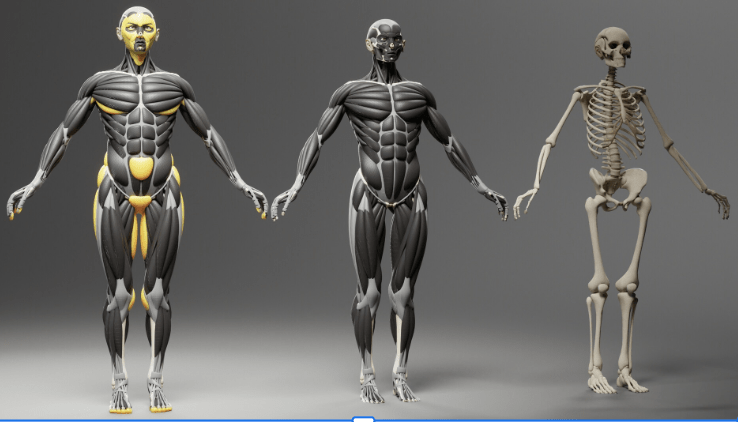

Skeletal muscle is often framed as machinery — motors, levers, contractile fibers. But this is far too small a story. Muscle is an immune organ, a sensor and signaler, constantly in conversation with the cells that determine healing, strength, and metabolic resilience.

Every contraction initiates an immune response.

Every repair cycle is an immune negotiation.

Every loss of muscle mass echoes through the immune system — changing its tone, its vigilance, and its inflammatory set point.

Myokines: Muscle’s Molecular Vocabulary

Muscle speaks its immune language through myokines, peptides released during contraction, damage, repair, or metabolic stress. Far from niche messengers, myokines orchestrate whole-body physiology.

IL-6 — The Janus-Faced Messenger

IL-6 is one of biology’s most misunderstood molecules.

Muscle-derived IL-6 (released during exercise):

- enhances glucose uptake

- stimulates AMPK

- promotes fat oxidation

- dampens systemic inflammation

- improves insulin sensitivity

Adipose-derived IL-6 (released chronically):

- activates hepatic CRP

- perpetuates low-grade inflammation

- worsens insulin resistance

- contributes to catabolic states seen in aging and chronic illness

Same molecule; different context; opposite physiological meaning.

This duality is central to why sarcopenia can tip the entire body toward inflammatory fragility:

Lose muscle → lose anti-inflammatory IL-6 → unmask inflammatory IL-6.

IL-15 — Muscle’s Mitochondrial Guardian

IL-15 regulates mitochondrial density and protects against atrophy.

It signals to immune cells — especially NK cells — supporting the metabolic tone of innate immunity.

Low IL-15 levels correlate with:

- reduced muscle mass

- impaired mitochondrial biogenesis

- heightened adiposity

- impaired immune surveillance

Irisin — The Exercise Messenger

Released from FNDC5 in contracting muscle, irisin:

- promotes browning of white adipose tissue

- enhances thermogenesis

- improves insulin sensitivity

- may cross the BBB to support synaptic plasticity

This is where movement becomes metabolism — and cognition.

Macrophages, T-cells, and the Cycle of Repair

Muscle regeneration depends on immune choreography:

Phase 1 — Pro-inflammatory cleanup (the necessary fire)

After microdamage or exercise-induced stress:

- M1 macrophages arrive first

- they clear debris, release cytokines, and recruit satellite cells

- they set the stage for regeneration

Without this inflammatory spark, muscle cannot remodel.

Phase 2 — Anti-inflammatory remodeling (the healing shift)

Hours later, M1 cells transition to M2 macrophages, releasing IL-10 and growth factors that:

- activate satellite-cell proliferation

- promote angiogenesis

- restore extracellular matrix integrity

This is the moment where repair becomes strength.

T-cells also play a surprisingly direct role: regulatory T-cells (Tregs) accumulate in injured muscle and secrete amphiregulin, promoting satellite-cell differentiation.

In aging, this T-cell support system weakens — part of the reason older adults repair more slowly.

When Inflammation Tips Toward Catabolism

Chronic inflammation — from aging, visceral adiposity, diabetes, cancer, or inactivity — disrupts this elegant choreography.

- M1 macrophages dominate.

- TNF-α and IL-1β suppress satellite-cell activation.

- NF-κB signaling increases muscle proteolysis.

- IL-6 shifts toward its inflammatory profile.

- Mitochondrial efficiency drops.

- Muscle protein synthesis falls despite normal nutrition.

This inflammatory impedance is a core driver of anabolic resistance — explaining why older adults and people with chronic disease require more protein, more stimulus, and more recovery time to achieve the same growth.

Sarcopenia is not just muscle loss.

It is an immune shift.

This is because muscle is not only the organ of motion–it is the immune system’s quiet partner, shaping inflammation, repair, metabolism, and resilience.

The Fat–Muscle–Bone Axis: EV Signaling, Atrogenes, and the Metabolic Immune Niche

Most people imagine fat, muscle, and bone as isolated departments:

storage, strength, structure.

But biology tells a different story.

These tissues are engaged in constant molecular conversation — using hormones, cytokines, mitochondrial fragments, lipids, and most importantly, extracellular vesicles (EVs) to influence one another’s fate.

The emerging truth is simple and radical: Body composition is a communication system, not a set of compartments. And these conversations determine whether the body moves towards health, resilience, and regeneration, or towards inflammation, catabolism, and frailty.

I. Adipose Tissue as a Signaling Organ — and Why EVs Changed the Game

White adipose tissue sends molecular messages into circulation.

In lean, metabolically healthy states, these signals support energy balance and immune stability.

But as adipose tissue becomes inflamed, its EV cargo changes, and those vesicles begin exporting dysfunction.

EVs from inflamed adipose tissue and adipose tissue macrophages (ATMs) carry:

- microRNAs (miR-27a, miR-29a, miR-155)

- inflammatory cytokine mRNA

- oxidized lipids

- mitochondrial DNA fragments

- proteins that trigger TLR/NF-κB inflammatory pathways

These vesicles fuse with distant organs, especially muscle, where they reprogram tissues epigenetically.

This is not symbolic language — it is literal genomic reprogramming of muscle cells by fat.

What Exactly Are Extracellular Vesicles (EVs)?

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are tiny membrane-bound packets released by nearly every cell in the body.

They function as molecular messengers, carrying cargo that can reshape the behavior of distant tissues.

EVs typically contain:

- microRNAs (miRs) — small regulatory RNAs that alter gene expression

- proteins — including enzymes, receptors, and signaling molecules

- lipids

- mitochondrial fragments

- inflammatory or metabolic signals

They circulate in blood, lymph, and interstitial fluid, fusing with recipient cells to reprogram them — modifying inflammation, metabolism, growth pathways, and even stem-cell fate.

EVs are the body’s covert communication network.

They explain how fat talks to muscle, how inflammation spreads, and how the metabolic tone of one organ influences the entire organism.

II. EVs from Adipose → Muscle: How Fat Drives Insulin Resistance and Atrophy

Human and animal studies show that obese or inflamed adipose tissue releases EVs that travel to skeletal muscle and cause:

1. Insulin Resistance

EV cargo downregulates:

- IRS-1 (insulin signaling)

- AKT phosphorylation

- GLUT4 expression

- PGC-1α (mitochondrial biogenesis)

This alters fuel handling and metabolic flexibility.

2. Mitochondrial Dysfunction

EV-delivered miRs impair:

- oxidative phosphorylation

- mtDNA integrity

- fusion/fission dynamics

3. Suppression of Muscle Growth Pathways

EV cargo inhibits:

- Akt–mTOR signaling (anabolic pathway)

- satellite-cell proliferation and differentiation

This creates a state of anabolic resistance.

4. Activation of Atrogenes (atrophy genes)

Inflammatory EVs activate FOXO1/3, which turn on the two canonical atrogenes:

- Atrogin-1 (MAFbx): ubiquitin ligase that marks structural muscle proteins for degradation

- MuRF1: targets myosin heavy chains and other contractile proteins

Upregulation of these atrogenes is a biochemical signature of:

- aging-related sarcopenia

- immobilization

- cachexia

- chronic inflammation

- glucocorticoid exposure

EVs are upstream triggers of FOXO → atrogin/MuRF1 activation.

This is one of the most important unifying mechanisms in modern muscle physiology.

What Are microRNAs (miRs)?

MicroRNAs are short, non-coding RNA sequences — typically 20–24 nucleotides long — that act as master regulators of gene expression.

They do not make proteins.

Instead, they turn genes on or off by:

- binding to messenger RNA (mRNA)

- blocking translation

- or triggering degradation of target mRNA

A single microRNA can regulate hundreds of genes, meaning small shifts in miR cargo can reshape entire cellular programs — including:

- inflammation

- mitochondrial function

- insulin signaling

- muscle growth or atrophy

- stem-cell differentiation

- cancer metabolism

When packaged inside EVs, microRNAs become long-distance molecular instructions, capable of turning a healthy tissue toward growth, repair, or — in pathological contexts — atrophy and metabolic dysfunction.

III. ATM-Derived EVs: Cross-Organ Sabotage

Adipose tissue macrophages in obesity become inflammatory hubs.

Their EVs are especially damaging. They:

- suppress satellite cell activation

- prolong chronic inflammation

- reduce regenerative potential

- accelerate muscle proteolysis

- modulate the bone marrow niche toward adipogenesis

ATM EVs are now considered a key driver of sarcopenic obesity, where fat mass rises while muscle quality and quantity collapse.

This is also one reason why weight loss without resistance training often worsens muscle loss — the inflammatory EV phenotype persists.

IV. Bone Marrow Fat, EVs, and the Anti-Regeneration Loop

Marrow adipose tissue (MAT) increases with:

- aging

- estrogen decline

- inactivity

- chronic inflammation

- glucocorticoids

MAT-derived EVs:

- suppress myogenesis

- promote adipogenesis from mesenchymal stem cells

- reduce osteoblast lineage commitment

- increase osteoclast activation

- degrade bone microarchitecture

The result is the classic triad seen in aging and chronic disease:

- more fat

- less muscle

- weaker bone

This is not coincidence — it is shared EV-driven fate programming.

V. Brown Fat EVs: The Protective Counterforce

In stark contrast to white fat, brown adipose tissue (BAT) releases EVs that:

- enhance mitochondrial biogenesis in muscle

- improve insulin sensitivity

- increase oxidative capacity

- promote thermogenesis

- carry “fit” molecular signatures that counter inflammatory networks

Emerging research suggests BAT EVs may even counteract some effects of aging, though this field is early.

VI. Exercise-Derived EVs: The Regenerative Broadcast

This is where physiology becomes symphony.

Contracting muscle releases EVs with:

- miR-1 (improves insulin sensitivity)

- miR-133 & miR-206 (muscle regeneration, satellite-cell activation)

- mitochondrial peptides

- myokines that speak to bone, fat, immune, and brain cells

Exercise EVs:

- stabilize the NMJ

- promote satellite-cell fusion

- dampen chronic inflammation

- improve metabolic flexibility

- enhance bone remodeling

- transmit pro-cognitive signals

- shift bone marrow away from adipogenesis

This is why movement is a systemic treatment, not a local one.

VII. Tumor-Derived EVs: The Engine of Cachexia

Tumors release EVs carrying:

- miR-21

- Hsp70/90 (heat shock proteins 70 and 90 — molecular chaperones that regulate protein folding and signal cellular stress)

- TLR4 activators

- oxidized lipids

- pro-inflammatory proteins

These EVs:

- activate NF-κB

- induce apoptosis in muscle

- increase ROS

- suppress protein synthesis

- activate atrogenes (atrogin-1, MuRF1)

- impair mitochondrial function

Cachexia is therefore not simply “malnutrition.”

It is EV-mediated reprogramming of muscle into a catabolic state, independent of caloric intake.

VIII. The Metabolic Immune Niche: A New Framework for Body Composition

What emerges from all of this is a systems model. Fat, muscle, and bone are in an EV-mediated metabolic-immune ecosystem. And that ecosystem determines:

- muscle regeneration or degeneration

- bone formation or loss

- fat expansion or browning

- inflammatory vs. reparative immune tone

- mitochondrial health

- the balance between anabolic and catabolic programs

Body composition is not static.

It is a living conversation — one we can influence through behavior, environment, hormones, and therapy.

Sex Hormones & Anabolic Resistance: The Endocrine Architecture of Muscle Repair

Muscle is not just fiber and force. It is an endocrine-responsive organ, exquisitely tuned to the hormonal environment. Testosterone, estrogen, and DHEA shape the willingness of muscle to grow, repair, and regenerate. When hormones decline — with aging, stress, chronic inflammation, or illness — the muscle system shifts from anabolic openness to defensive conservation.

This shift is one of the deepest roots of anabolic resistance.

I. Testosterone: Amplifier of the Anabolic Signal

Testosterone is not simply a “male” hormone — it is a repair signal that acts at every level of muscle biology.

It increases:

- satellite-cell activation

- myonuclear accretion

- IGF-1 signaling

- Akt–mTOR pathway strength

- protein synthesis

- muscle fiber cross-sectional area

It decreases:

- myostatin

- FOXO-driven atrogene expression

- inflammatory cytokine sensitivity

Even small, age-related declines produce measurable changes in:

- muscle mass

- strength

- recovery time

- mitochondrial function

- exercise tolerance

In both sexes, low testosterone correlates with:

- increased fat mass

- reduced muscle density

- slower repair

- higher inflammatory tone

Testosterone deficiency is not cosmetic — it is metabolic.

II. Estrogen: The Hidden Architect of Muscle Repair

Estrogen’s importance in muscle health is profoundly under-recognized, especially in popular science and even in parts of the fitness industry.

Estrogen modulates muscle physiology through:

1. Nitric Oxide (NO) Signaling

Estrogen increases endothelial NO synthase activity → improved blood flow, oxygenation, and nutrient delivery to muscle.

2. Immune Modulation

Estrogen tempers inflammatory cytokines and supports:

- macrophage M2 polarization

- faster inflammatory resolution

- more coordinated repair

3. Satellite-Cell Activation

Estrogen enhances:

- satellite-cell proliferation

- differentiation

- fusion into existing fibers

Its absence after menopause is one reason muscle repair slows even when exercise habits remain constant.

4. Mitochondrial Protection

Estrogen improves:

- mitochondrial biogenesis

- membrane stability

- antioxidant capacity

- metabolic flexibility

When estrogen declines, mitochondrial fragmentation and ROS accumulation increase — a precondition for anabolic resistance.

The clinical reality:

Hormone loss in menopause contributes to:

- slower adaptation to exercise

- more soreness

- less hypertrophy

- greater intramuscular fat

- more inflammation

This is physiology, not willpower.

III. DHEA: The Local Androgen Reservoir

DHEA circulates in far higher concentrations than testosterone, especially in women.

Skeletal muscle expresses enzymes that convert DHEA → testosterone or estradiol locally, allowing muscle to fine-tune its hormonal environment.

Functions of DHEA in muscle include:

- supporting IGF-1 signaling

- enhancing mitochondrial efficiency

- moderating inflammation

- contributing to NMJ health

- preserving muscle density

DHEA levels decline steadily with age, lowering the hormonal “baseline” from which anabolic signals must act.

This is one reason older adults require:

- higher protein intake

- higher training stimulus

- longer recovery windows

The endocrine background is simply quieter.

IV. Hormones and the EV Signal: The New Layer

Hormonal decline shifts the EV signature of fat, muscle, and bone.

Low estrogen and low testosterone are associated with:

- increased release of inflammatory EVs

- higher expression of miR-155 and other catabolic miRs

- reduced EV cargo that promotes mitochondrial biogenesis

- weaker satellite-cell activation

- impaired osteoblast signaling

- greater marrow adiposity (MAT) EV output

Hormones determine the “tone” of the entire metabolic-immune niche, including the messages tissues send to one another.

V. The Central Problem: Anabolic Resistance

Anabolic resistance is defined as a reduced ability of muscle to synthesize protein and grow in response to stimuli (exercise, food, hormones).

Hormonal decline triggers anabolic resistance by:

- blunting the mTOR response

- decreasing amino acid uptake

- slowing satellite-cell activation

- increasing inflammatory sensitivity

- activating FOXO → atrogin-1/MuRF1 pathways

- reducing NMJ stability

- decreasing mitochondrial efficiency

Even with adequate protein and training, the signal-to-noise ratio collapses.

This is why:

- older adults need higher protein doses (2–3x the mTOR activation threshold of youth)

- resistance training must be progressive and intentional

- recovery demands increase

- sleep becomes critical

- hormonal therapy can dramatically alter outcomes

VI. Why Hormones Matter for Cachexia and Sarcopenia

In cancer, CHF, COPD, and chronic illness:

- testosterone plummets

- estrogen signaling is disrupted

- DHEA falls sharply

These hormonal collapses amplify:

- inflammatory EV patterns

- atrogene activation

- mitochondrial fragmentation

- NMJ degeneration

This is why cachexia progresses even when patients are fed adequately.

The hormonal–immune–EV system is in a pro-catabolic lock.

Hormones set the volume of the anabolic signal. When the volume is too low, muscle doesn’t pick up the message to grow.

VII. Aromatase: When Testosterone Needs to Become Estrogen

Testosterone does not act alone in muscle. A crucial portion of its effects are mediated through aromatization — conversion of testosterone → estradiol (E2) by the enzyme aromatase, expressed in adipose tissue, brain, and importantly, in muscle itself.

This matters because:

- In both animals and humans, blocking aromatase (with aromatase inhibitors)

– reduces estradiol levels,

– blunts muscle-protein synthesis,

– and impairs hypertrophy even in the presence of high circulating testosterone.

Put simply, without estradiol, testosterone’s full anabolic potential is never realized.

This is particularly relevant for:

- men on aromatase inhibitors (for infertility, gynecomastia, or “optimization”)

- athletes misusing AIs to keep estrogen “low”

- older men whose aromatase activity and estradiol levels are suppressed aggressively

In these cases, muscle is bathed in testosterone but deprived of one of its key downstream signals.

VIII. Rethinking Androgen Deprivation: The Case for Estradiol

In androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) for prostate cancer, testosterone is driven very low to suppress tumor growth. Traditionally, this has meant accepting:

- rapid muscle loss

- increased fat mass

- insulin resistance

- bone loss

- increased CV risk

- marked declines in quality of life

But estradiol is not simply an accessory. It:

- protects bone

- preserves muscle

- improves lipid profiles

- modulates vascular tone and endothelial function

- supports metabolic flexibility

Several lines of research suggest that estradiol replacement (or selective estrogen receptor modulation) during ADT may:

- attenuate muscle loss

- protect bone density

- improve cardiometabolic risk

— without meaningfully raising intraprostatic androgen signaling, especially if androgens are adequately suppressed.

The translational implication is important, In some contexts, it may be safer and smarter to preserve estradiol for muscle and cardiovascular protection, even when we must suppress testosterone for oncologic reasons.

This reframes sex hormones not as simple “male vs female” molecules, but as integrated signals that jointly govern the anabolic environment of muscle, bone, and the vascular system.

Recovery as Signal: When the Body Says “Grow,” “Hold,” or “Break”

Recovery is not the absence of training.

It is a biological negotiation, a complex decision-making process the body conducts after every bout of stress.

Muscles do not grow because we train.

Muscles grow because the body interprets the stimulus as safe, reparable, and worth adapting to.

This distinction is everything.

It could never happen to me. I had a strict sleep and meal schedule that paced my training. I meditated, stretched, did mobility work and had a day off dancing each week (mostly). I was safe from overtraining.

That, sadly, was my very own Blind Spot in the Johari Window model. My friends thought I was “doing a lot” but I thought I needed to do more. When I finally had to stop dancing because I could no longer hide my injuries (limping through the choreography was just too obvious–oddly, I didn’t even have pain for quite a while, or, more accurately, I wasn’t able to perceive the pain for quite a while. It took people coming up to me to ask what was wrong because I was limping for me to take stock of what was happening in my body.)

And then, when I tried to rehab, I approached it like I was still training. 2 sets? No problem, 4 or 6 sets should be better. 10 lbs? Should be able to do 15 at least. Alternate the exercises? Why not just stack them and do them all? The result–a worsening of symptoms to the point where I could barely walk.

I finally had to face the fact that I had over-trained and that I needed to STOP. Not reduce my workout, but Stop altogether. I gave in because, well, I had to. I couldn’t even get out of bed because I was so exhausted. I had to give myself permission to lie in and rest, to sleep the long, long hours that my body demanded (9-10 hours), and to just do–nothing. This issue on muscle health is very personal to me because for years I thought I had been doing things the right way, that I should push harder and challenge myself.

What I’ve learned (the painful way) is that it’s not how hard you train, it’s how well you recover that matters. That recovery is a science and a discipline in itself. It is not just “resting”. It is a program of repair and regeneration that our bodies need. If the onslaught of daily physical demands exceeds the body’s ability to rebuild, the net result is catabolic decline.

That’s why, if you don’t read anything else in this issue, I hope you’ll read this section and take it to heart.

I. Recovery Is a Signal, Not a Timeline

Textbook advice often frames recovery as “48–72 hours” — but muscles do not operate on a schedule. They operate on signals:

- Is inflammation resolving?

- Are immune cells shifting from M1 (cleanup) → M2 (repair)?

- Has neuromuscular drive returned?

- Is mitochondrial efficiency stabilizing?

- Has the hormonal and autonomic environment normalized?

Each of these is not a single event but a physiological “vote.”

When enough votes align, the body grants permission for adaptation.

When they do not, the body protects itself by blunting adaptation — anabolic resistance as an act of self-preservation.

II. The Biomarkers of Readiness: When the Body Is Actually Prepared for Growth

You can detect recovery not by counting hours, but by reading patterns.

1. Strength Return (~90%)

One of the most reliable practical markers.

If your strength in a movement is:

- ≥ 90% of baseline → nervous system has recovered

- < 90% → central fatigue and peripheral repair processes are still incomplete

This is more informative than soreness or time since training.

Why strength is so revealing:

Under-recovered muscle shows characteristic neuromuscular deficits:

- reduced motor-unit firing rates

- impaired rate coding

- diminished recruitment of high-threshold motor units

- poor synchronization on EMG

These electrical signatures directly correlate with the felt experience of sluggishness or “signal dropout.”

Additionally, tendons — which undergo microstructural changes with heavy loading — temporarily lose viscoelastic stiffness. This alters:

- force transmission efficiency

- proprioceptive feedback

- joint timing

As collagen re-aligns and stiffness returns, athletes experience that unmistakable “pop”: power feels crisp again.

Strength return is the body’s democratic consensus: We can load this again.

2. Heart Rate Variability (HRV)

Recovery correlates with parasympathetic rebound.

You’re ready when:

- HRV returns to or exceeds baseline

- resting HR normalizes

- sympathetic “tension” decreases

But HRV is affected by far more than training load:

- poor sleep

- caloric deficit

- dehydration

- illness

- psychological stress

- circadian disruption

- menstrual cycle phase

HRV is not a training score — it is a physiological burden score.

Low HRV + elevated resting HR generally signals unresolved stress.

3. Subjective Muscle Tension and “Feel”

Elite athletes describe “readiness” before it can be measured.

This subjective interoception correlates with:

A. EMG recruitment efficiency

When under-recovered:

- firing frequency drops

- high-threshold motor units hesitate

- synchronization falters

This is why movements feel uncoordinated, dull, or “heavy.”

B. Tendon stiffness profiles

Temporary reductions in stiffness change proprioceptive timing and force transfer — a shift that is deeply felt.

As stiffness normalizes, movement regains sharpness. Athletes often describe this moment as the body “coming back online.”

The body tells the truth if you learn its language.

4. IL-6 Trajectory

During exercise, muscle-derived IL-6 rises as a beneficial internal energy sensor.

This IL-6 is produced proportionally to glycogen depletion — making it a signal of metabolic strain, not inflammation.

How muscle senses IL-6

Skeletal muscle expresses membrane-bound IL-6 receptors (IL-6R), allowing for classical signaling during exercise:

- IL-6 binds IL-6R

- signals through gp130

- activates AMPK

- increases glucose uptake (GLUT4 translocation)

- enhances fatty-acid oxidation

- suppresses TNF-α

This is adaptive, anti-inflammatory IL-6 — not the chronic inflammatory trans-signaling seen in disease.

Why IL-6 decline signals readiness

After recovery:

- glycogen stores are restored

- muscle ceases IL-6 production

- circulating IL-6 returns to baseline

But persistently elevated IL-6, CRP, or TNF-α indicates unresolved inflammation → a compromised anabolic window.

5. Creatine Kinase (CK)

CK rises after eccentric training but should drop within 24–72 hours.

Patterns matter:

- High CK + restored strength → normal adaptation

- High CK + suppressed strength → unresolved microdamage

- Chronic elevation → poor recovery or impending injury

And an important distinction:

- CK in the thousands after hard training is common.

- CK >10,000 (with dark urine, severe pain, swelling) suggests rhabdomyolysis, a medical emergency — not simply “overtraining.”

CK is not about the number — it’s about the story the number tells.

III. Overreaching vs. Overtraining: Different Worlds

People (myself included!) often conflate these, but they are physiologically distinct.

Functional Overreaching

- Temporary dip in performance

- Exaggerated rebound after rest

- Increased HRV variability

- Mitochondria upregulate once stress is removed

- Immune system strained but not impaired

This is the athletic sweet spot — controlled stress that leads to supercompensation.

Nonfunctional Overreaching

- Longer performance slump

- No rebound

- Mood and motivation decline

- Inflammatory cytokines remain elevated

- NMJ efficiency begins to decline

Overtraining Syndrome

A multi-system crash:

- chronically low HRV

- reduced catecholamine responsiveness

- low testosterone

- low estradiol

- high cortisol with flattened diurnal rhythm

- mitochondrial dysfunction and fragmentation

- persistent atrogene activation (atrogin-1, MuRF1)

- disrupted sleep-stage architecture

- NMJ inefficiency → reduced motor-unit activation

- depressive or anxious symptoms

- decreased immune surveillance

Recovery here is not days — it is months, and sometimes years.

This is not fatigue.

It is a physiological refusal: “We cannot afford more stress.”

IV. Immune Resolution: The Real Gatekeeper of Muscle Growth

The repair cycle requires an elegant immune choreography:

- M1 macrophages arrive to clear debris

- They transition toward M2 macrophages to build tissue

- Satellite cells proliferate and differentiate

- Fascia and tendon remodel

- Inflammation resolves

- Regeneration begins

If M1 → M2 transition is delayed (aging, poor sleep, chronic stress, chronic inflammation, inadequate nutrition), muscle cannot enter the anabolic phase.

This is a major cause of “mysterious plateaus” and stalled progress, particularly in aging and chronic disease.

V. Recovery Debt: The Silent Sinkhole of Performance

You can train intensely, or you can accumulate recovery debt —

but you cannot do both for long.

Recovery debt includes:

- insufficient sleep

- chronic inflammation

- hormonal insufficiency

- unresolved microdamage

- persistent sympathetic activation

- inadequate energy or protein

- suboptimal mitochondrial support

Each of these lowers the signal-to-noise ratio for anabolic signaling, turning even excellent training into diminishing returns.

Recovery isn’t optional.

It is the currency of adaptation.

VI. Why This Matters for Sarcopenia and Aging

Older adults often do not lack effort — they lack signal clarity.

Age brings:

- slower immune resolution

- reduced sex hormone tone

- elevated baseline inflammation

- diminished mitochondrial efficiency

- slower satellite-cell activation

- greater exposure to catabolic EV signaling

This means:

- heavier reliance on recovery

- longer windows between anabolic opportunities

- greater sensitivity to sleep deficits

- narrower margins for error

Training still works — but recovery becomes the rate-limiting step.

VII. Overtraining Syndrome — When Recovery Collapses

Overtraining Syndrome (OTS) is not about doing “too much training.”

It is a multi-system derangement, a failure of the body’s capacity to return to baseline after repeated stress — physical, emotional, metabolic, or all three.

It reflects a breakdown across:

- autonomic regulation (low HRV, elevated resting HR, sympathetic overdrive)

- hormonal integrity (low estradiol, low testosterone, altered cortisol rhythm)

- NMJ efficiency (impaired motor-unit recruitment and central drive)

- mitochondrial capacity (fragmentation, reduced ATP production)

- immune balance (elevated IL-6/TNF-α, poor macrophage resolution)

- sleep architecture (loss of deep sleep, REM instability)

- psychological tone (irritability, anxiety, emotional flattening)

- atrogenic activation (atrogin-1, MuRF1) signaling ongoing catabolism

OTS is the body declaring:

“We are no longer capable of repairing what you’re demanding of us.”

And unlike ordinary fatigue, the timeline is prolonged.

What OTS Feels Like

People with OTS consistently describe:

- waking unrefreshed, no matter how long they slept

- feeling “hollow” or “wired but tired”

- inability to generate power despite strong will

- emotional volatility or, conversely, emotional numbness

- unusually slow recovery from minor stressors

- declining coordination, balance, or fluidity

- sense of disconnection from one’s body or performance identity

The CNS interprets effort as threat.

Motivation drops not because the person is weak —

but because physiology no longer supplies the capacity to want.

Recovery From OTS: A Phased Physiological Reset

OTS resolves in phases, not linearly, and each system recovers at its own pace.

These timelines are drawn from sports medicine studies, military overtraining data, endocrine recovery curves, and clinical experience with exhausted physicians, dancers, and endurance athletes.

Expect oscillations, not clean lines.

Phase 1 — Nervous System Unloading (2–6 weeks)

Goal: Remove the threat signal. REMOVE, not reduce. This means STOP your exercise/training regimen.

What happens physiologically:

- sympathetic tone begins to downshift

- resting HR starts to fall

- HRV begins creeping upward

- sleep deepens slightly (more slow-wave intrusions)

- cortisol begins normalizing, but remains volatile

What you feel:

- more spontaneous yawning or sleepiness

- mild emotional stabilization

- moments of clarity breaking through the fog

- reduced startle response

- beginning signs of strength return, but inconsistent

This is not the time to “test” yourself.

The fragile recovery of the autonomic system requires protection.

Phase 2 — Hormonal & Immune Rebalancing (1–3 months)

Goal: Re-establish anabolic capacity.

Physiology:

- estradiol/testosterone begin slowly rising

- cortisol diurnal curve stabilizes

- thyroid function often improves

- atrogenes (atrogin-1, MuRF1) begin downregulating

- inflammatory cytokines begin normalizing

- immune resilience increases (fewer colds, fewer flares)

What you feel:

- mornings feel less punishing

- mood becomes more predictable

- small movements — a walk, light mobility — feel nourishing, not draining

- strength becomes more consistent

- fewer emotional overreactions to small stressors

This is when the body finally believes it is safe enough to consider rebuilding.

Phase 3 — Mitochondrial Repair & NMJ Restoration (2–6 months)

Goal: Rebuild energy systems and re-establish neuromuscular precision.

Physiology:

- mitochondrial biogenesis increases

- ATP availability improves

- lactate clearance normalizes

- NMJ efficiency rebounds (better central drive, rate coding, synchronization)

- tendon stiffness gradually restores

- movement quality begins to sharpen again

What you feel:

- the “heavy limbs” sensation decreases

- coordination returns

- body awareness resurfaces

- training finally feels like training, not punishment

This is the phase where many people make the mistake of pushing too hard too soon.

The capacity for load increases, but the tolerance to cumulative stress lags behind.

Phase 4 — Reconditioning & Return to Load (4–12 months)

Goal: Reintroduce training in a way the body recognizes as opportunity, not threat.

Physiology:

- autonomic, hormonal, and mitochondrial systems resume communicating coherently

- AMPK and mTOR regain appropriate oscillation

- recovery timelines shorten

- inflammatory responses scale appropriately

- satellite-cell activation improves

What you feel:

- real strength gains

- stable energy

- emotional resilience

- renewed desire to train

- feeling “yourself” again

This is the phase where identity returns — the part of you that moves, creates, trains, and performs without fear of collapse.

The Most Important Truth About OTS Recovery

Recovery is not linear.

You will have weeks that feel like leaps forward, and days that feel like relapses.

The timeline is not the enemy. Impatience is.

And the end point of OTS recovery is not merely “getting back to where you were,”

but emerging with:

- a more resilient autonomic system

- a better understanding of your stress load

- a higher recovery ceiling

- the ability to read your body with unprecedented precision

Overtraining is not excess effort. It is effort applied in a body that can no longer repair.

One of the things I have noticed about my body while recovering from OTS is the increased need for sleep. Let’s take a look at why this is so important.

Sleep: The Anabolic Night

Sleep is not rest.

It has an architecture — an engineered biological sequence in which every stage performs a specific anabolic and reparative task.

If exercise is the stimulus, and recovery is the decision, then sleep is the execution of that decision.

The body waits until nightfall to rebuild the damage of the day.

I. Deep Sleep: Where Muscle Repair Actually Happens

The most important stage for muscle growth and metabolic recovery is slow-wave sleep (SWS), also known as deep NREM sleep.

During SWS:

1. Growth hormone (GH) surges

The largest pulse of GH in a 24-hour cycle occurs in the first SWS cycle.

GH:

- stimulates IGF-1 production

- promotes muscle protein synthesis

- enhances tendon and collagen turnover

- accelerates satellite-cell activation

- increases fat oxidation

This is why sleep restriction dramatically blunts anabolic signaling even when training is unchanged.

2. IL-6 shifts into its reparative mode

Unlike inflammatory IL-6 (trans-signaling), nighttime IL-6 oscillations:

- aid tissue repair

- support immune recalibration

- reduce oxidative stress

Sleep is the biological context that determines whether IL-6 heals you or harms you.

3. M1 → M2 macrophage transition completes

If this transition fails, inflammation lingers into the next day.

If it completes, muscle enters a true anabolic window.

Sleep is the difference between “I’m still wrecked” and “My body absorbed that.”

II. Melatonin: The Most Misunderstood Hormone in Physiology

Melatonin is often dismissed as a “sleep hormone.”

In reality, it is a mitochondrial and immune modulator with profound implications for muscle. (I might do a full issue on Melatonin in the future–let me know if there’s an interest.)

Melatonin: What it actually does

- enhances oxidative phosphorylation

- decreases ROS (reactive oxygen species)

- stabilizes mitochondrial membranes

- increases mitochondrial fusion

- promotes satellite-cell proliferation

- dampens chronic inflammation

- improves insulin sensitivity

In muscle, melatonin is not sedating — it is anabolic.

Why modern life threatens melatonin signaling

- evening screens suppress endogenous melatonin

- late eating shifts circadian alignment

- blue-spectrum LEDs delay onset

- nighttime sympathetic activation blunts its amplitude

Melatonin is a darkness-dependent repair molecule.

Without darkness, the deepest forms of muscle recovery cannot occur.

III. Sleep Restriction: The Fastest Way to Lose Muscle Without Moving Less

The literature is astonishingly consistent:

Just 4–5 nights of sleep restriction

(~5 hours per night)

→ 20–30% reduction in muscle protein synthesis

→ decreased testosterone

→ decreased estradiol in women

→ reduced glucose tolerance

→ increased cortisol

→ increased IL-6 (inflammatory)

→ reduced AMPK sensitivity

→ impaired mitochondrial bioenergetics

And the kicker:

These deficits occur even if training volume is unchanged.

Sleep loss places the body into a subtle catabolic state where:

- atrogenes activate

- NMJ efficiency decreases

- central drive is impaired

- recovery debt accumulates rapidly

Muscle does not regress because you didn’t train.

It regresses because you didn’t sleep.

IV. REM Sleep: Where the Brain Rehearses Movement

REM is not reparative for muscle —it is reparative for skill.

Neurologically:

- motor engrams consolidate

- procedural memory reorganizes

- synaptic pruning optimizes efficiency

- neuromuscular coordination refines in the absence of movement

This is why dancers, musicians, and elite athletes experience REM-dense nights after learning new choreography or complex skills.

Skill ≠ strength.

Skill is REM-dependent plasticity.

V. Circadian Biology: Why “When” You Sleep Determines “How” You Recover

Circadian alignment affects:

- GH amplitude

- cortisol rhythm

- melatonin secretion

- body temperature drops (essential for SWS)

- mitochondrial metabolic cycles

- nighttime insulin sensitivity

- immune recalibration

Two key insights:

- Sleep before midnight is disproportionately more anabolic, because SWS is front-loaded.

- Circadian misalignment (shift work, irregular schedules) induces muscle insulin resistance even in fit individuals.

You can do everything right — strength training, protein intake, perfect programming, all that good stuff — and still lose muscle if your circadian rhythm is misaligned.

VI. Why Older Adults Are in a Sleep-Recovery Double Bind

Aging reduces:

- amplitude of melatonin secretion

- depth of slow-wave sleep

- nighttime GH pulses

- mitochondrial efficiency

- immune resolution speed

Meaning older adults need recovery more than younger adults but get less of it.

This is one reason sarcopenia accelerates in the 60s–70s: their nights no longer fully repair their days.

VII. Sleep and Overtraining: The Vicious Loop

Sleep loss → overtraining physiology

Overtraining physiology → sleep loss

The loop is self-reinforcing:

- sympathetic activation prevents deep sleep

- poor sleep elevates cortisol

- high cortisol blunts GH

- low GH impairs muscle recovery

- impaired recovery increases sympathetic tone

Breaking this loop is often the first step in reversing OTS.

VIII. Practical Anchors (Evidence-Based, Not Trend-Based)

(Not hacks — physiologic anchors.)

1. Fixed wake time

Most powerful circadian entrainer.

2. Darkness the hour before bed

Allows natural melatonin rise.

3. Cool environment for deeper SWS

Because core temperature drop is a sleep initiator.

4. Avoid late-night exercise

Elevates epinephrine and core temperature.

5. Manage pre-bed rumination

Sympathetic activation is a sleep killer.

6. Protein timing matters less than sleep timing

A rested body uses protein better than a tired one.

It helps to remember that sleep is not the absence of wakefulness. Rather, it is the presence of repair.

Recovery Modalities: What Actually Works, What Probably Helps, and What’s Hype

I. A Framing Principle: Recovery Is a Biological Outcome, Not a Sensation

Most recovery modalities are marketed around how they feel.

But recovery is not comfort.

Recovery is resolution:

- immune resolution

- autonomic rebalancing

- mitochondrial repair

- connective-tissue remodeling

- neuromuscular recalibration

A modality can feel good and still fail to meaningfully advance recovery.

Conversely, some of the most effective recovery signals are not immediately pleasant.

So we evaluate each modality by a single question: Does it improve the biological conditions required for adaptation?

II. Cold Exposure & Cryotherapy

The claim

- Reduces inflammation

- Speeds recovery

- Improves performance readiness

What the data actually show

Cold exposure does acutely reduce pain and perceived soreness by:

- vasoconstriction

- reduced nerve conduction velocity

- transient suppression of inflammatory signaling

However, repeated cold exposure immediately after resistance training has been shown to:

- blunt mTOR signaling

- reduce satellite-cell activation

- impair long-term hypertrophy gains

In other words:

cold can improve how you feel while impairing what you’re trying to build.

Where cold may be appropriate

- During competition phases when soreness reduction > adaptation

- In acute inflammatory flares

- For pain modulation, not growth

Wellth-e verdict: Useful for symptom (pain) control. Potentially counterproductive for muscle growth if used chronically post-training.

*** Would not recommend with OTS (and not just because of my personal dislike of the cold) as we need sympathetic down-regulation for recovery from OTS.

III. Infrared & Red-Light Therapy (Photobiomodulation)

The claim

- Enhances mitochondrial function

- Reduces inflammation

- Accelerates tissue repair

What the science suggests

Photobiomodulation acts primarily via:

- cytochrome c oxidase activation

- improved mitochondrial membrane potential

- increased ATP availability

- reduced oxidative stress

Small studies suggest improvements in:

- muscle fatigue resistance

- recovery kinetics

- delayed-onset muscle soreness

But effects are dose-, wavelength-, and context-dependent, and human performance data remain heterogeneous.

Where it may help

- mitochondrial insufficiency

- chronic inflammatory states

- aging muscle

- recovery-limited individuals

Wellth-e verdict: Biologically plausible, modestly supported and promising, but not a replacement for sleep, nutrition, or load management. Get those in first, and then you can play with light therapy.

IV. Compression Boots & Pneumatic Devices

The claim

- Flush metabolic waste

- Improve circulation

- Speed recovery

Physiology check

Compression increases venous return and may:

- reduce edema

- improve subjective soreness

- enhance parasympathetic tone

However, metabolite clearance is not the primary limiter of recovery in most people.

Muscle adaptation is limited more by:

- immune resolution

- mitochondrial recovery

- neuromuscular readiness

Where compression helps

- prolonged travel

- edema-prone individuals

- subjective comfort

- recovery between closely spaced events

Wellth-e verdict: Helpful for comfort and circulation. Neutral for hypertrophy and strength adaptation.

V. Percussive Therapy & Massage Guns

The claim

- Break up adhesions

- Increase blood flow

- Improve recovery

What they actually do

Percussive devices primarily affect:

- mechanoreceptors

- local pain modulation

- muscle tone via reflex pathways

They do not remodel fascia, but they do:

- reduce perceived stiffness

- improve range of motion

- downshift sympathetic tone

When they help

- pre-training neuromuscular priming

- post-training soreness modulation

- improving movement confidence

Wellth-e verdict: Effective for neural and perceptual recovery. Minimal direct impact on tissue repair. (Feels good though!)

VI. Stretching: Often Misunderstood, Occasionally Useful

Static stretching

- improves range of motion

- temporarily reduces force output if done pre-training

- little evidence for accelerating muscle repair

Dynamic mobility

- improves neuromuscular coordination

- supports tendon health

- enhances movement quality

Where stretching fits

Stretching is not a recovery tool for muscle damage.

It is a movement-quality tool that supports long-term joint and tendon health.

Wellth-e verdict: Useful for maintaining capacity. Not a substitute for recovery.

VII. The Modalities That Matter Most (Unsexy but Powerful)

Across studies, the strongest recovery signals remain:

- sleep quantity and quality

- circadian alignment

- adequate energy and protein

- autonomic downshifting

- load management

Everything else is additive at best.

If those are missing, no device will save you.

VIII. The Deeper Truth

Recovery tools are most effective when they:

- support the nervous system

- reduce unnecessary stress

- enhance signal clarity

They fail when they are used to override warning signs.

A body that needs more recovery does not need more tools.

It needs less threat. (Read that 10X)

Thus, recovery modalities should support adaptation, not anesthetize the warning signals that protect it.

From Mechanism to Meaning: Why Muscle Biology Forces a Rethink of Medicine

If there is a single lesson running through the science of sarcopenia, cachexia, and muscle loss, it is this:

Muscle does not fail because it is weak.

It fails because the signals governing repair, immunity, energy, and coordination fall out of alignment.

This matters — not just biologically, but structurally — because much of modern medicine is still organized around isolated targets.

We block a receptor.

We activate a pathway.

We suppress an inflammatory signal.

We replace a hormone.

And yet, across sarcopenia, cancer cachexia, chronic disease, and aging, the outcomes remain stubbornly incomplete.

Muscle mass may increase — but strength does not.

Biomarkers may improve — but function does not.

Interventions succeed in trials — but fail in lived bodies.

What the science in this issue reveals is not a lack of innovation, but a mismatch between problem and paradigm.

Why Single-Target Solutions Keep Underperforming

The emerging biology of muscle makes something uncomfortable clear:

- Myostatin inhibition can increase mass, but cannot restore neuromuscular precision.

- Androgen modulation can stimulate growth, but cannot substitute for immune resolution.

- AMPK activation can mimic metabolic signals, but cannot reproduce mechanical loading.

- Anti-inflammatory strategies can quiet cytokines, but disrupt repair if applied bluntly.

- Even advanced biologics struggle when recovery, sleep, and circadian alignment are ignored.

These are not failures of technology.

They are failures of integration.

Muscle sits at the crossroads of systems medicine:

- immune

- endocrine

- neural

- metabolic

- mechanical

- circadian

Treating it as a downstream tissue — rather than a coordinating organ — guarantees partial success at best.

A Quiet Shift Is Already Underway

The most promising directions in muscle medicine are no longer asking:

“How do we grow muscle faster?”

They are asking:

- How do we restore immune resolution?

- How do we quiet catabolic signaling without impairing surveillance?

- How do we preserve neuromuscular communication?

- How do we support recovery capacity across age and disease?

- How do we identify who is capable of adaptation — and who is not?

This shift reframes therapy from forcing outcomes to rebuilding conditions.

And once you see this, it becomes impossible to unsee its implications.

What Comes Next Is Not Just Scientific

If muscle health depends on coordination — not compliance — then the consequences extend far beyond physiology.

They touch:

- how clinical trials are designed

- how rehabilitation is reimbursed

- how aging is managed

- how cancer care measures success

- how performance medicine is practiced

- how recovery is valued (or ignored) in modern life

The science in Probe does not end in the lab.

It points directly toward a reckoning in how we define effectiveness, value, and progress in medicine.

We shall look at that reckoning in Prosper.

References

Pedersen, B. K., & Febbraio, M. A. (2008). Muscle as an endocrine organ: Focus on muscle-derived interleukin-6. Physiological Reviews, 88(4), 1379–1406.

https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.90100.2007

Pedersen, B. K., & Febbraio, M. A. (2012). Muscles, exercise and obesity: Skeletal muscle as a secretory organ. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 8(8), 457–465.

https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2012.49

Hojman, P., et al. (2011). IL-6 release from muscle during exercise: Role of energy sensing. Journal of Physiology, 589(24), 5917–5931.

Febbraio, M. A., & Pedersen, B. K. (2002). Muscle-derived interleukin-6: Mechanisms for activation and possible biological roles. FASEB Journal, 16(11), 1335–1347.

Nielsen, A. R., et al. (2007). IL-15 regulates muscle–fat cross-talk. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism, 293(2), E513–E519.

Boström, P., et al. (2012). A PGC1-α–dependent myokine that drives brown-fat–like development of white fat. Nature, 481(7382), 463–468.

https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10777

Tidball, J. G. (2017). Regulation of muscle growth and regeneration by the immune system. Nature Reviews Immunology, 17(3), 165–178.

https://doi.org/10.1038/nri.2016.150

Arnold, L., et al. (2007). Inflammatory monocytes recruited after skeletal muscle injury switch into anti-inflammatory macrophages to support myogenesis. Journal of Experimental Medicine, 204(5), 1057–1069.

Bonaldo, P., & Sandri, M. (2013). Cellular and molecular mechanisms of muscle atrophy. Disease Models & Mechanisms, 6(1), 25–39.

https://doi.org/10.1242/dmm.010389

Argilés, J. M., Busquets, S., Stemmler, B., & López-Soriano, F. J. (2014). Cachexia and sarcopenia: Mechanisms and potential targets. Current Opinion in Pharmacology, 22, 100–106.

Bodine, S. C., et al. (2001). Identification of ubiquitin ligases required for skeletal muscle atrophy. Science, 294(5547), 1704–1708.

https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1065874

Sandri, M. (2008). Signaling in muscle atrophy and hypertrophy. Physiology, 23(3), 160–170.

Meeusen, R., et al. (2013). Prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of the overtraining syndrome. European Journal of Sport Science, 13(1), 1–24.

https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2012.730061

Budgett, R. (1998). Fatigue and underperformance in athletes: The overtraining syndrome. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 32(2), 107–110.

Plews, D. J., et al. (2013). Training adaptation and heart rate variability in elite endurance athletes. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 113(2), 372–381.

Shaffer, F., & Ginsberg, J. P. (2017). An overview of heart rate variability metrics and norms. Frontiers in Public Health, 5, 258.

Brancaccio, P., Maffulli, N., & Limongelli, F. M. (2007). Creatine kinase monitoring in sport medicine. British Medical Bulletin, 81–82, 209–230.

Dattilo, M., Antunes, H. K. M., Medeiros, A., et al. (2011). Sleep and muscle recovery: Endocrine and molecular basis. Medical Hypotheses, 77(2), 220–222.

Morselli, L., et al. (2010). Impact of sleep deprivation on metabolic and endocrine function. The Lancet, 375(9711), 143–152.

Reiter, R. J., et al. (2014). Melatonin as an antioxidant: Under promises but over delivers. Journal of Pineal Research, 61(3), 253–278.

Srinivasan, V., et al. (2011). Melatonin in skeletal muscle health. Journal of Pineal Research, 51(1), 1–17.

Karsenty, G., & Olson, E. N. (2016). Bone and muscle endocrine functions. Cell, 164(6), 1248–1256.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.043

Craft, C. S., Robinson, M. E., & Katzman, W. B. (2018). Bone marrow adipose tissue. Current Osteoporosis Reports, 16(5), 541–549.

Théry, C., Zitvogel, L., & Amigorena, S. (2002). Exosomes: Composition, biogenesis and function. Nature Reviews Immunology, 2(8), 569–579.

Thomou, T., et al. (2017). Adipose-derived circulating microRNAs regulate gene expression in other tissues. Nature, 542(7642), 450–455.

https://doi.org/10.1038/nature21365

Sabaratnam, R., et al. (2020). Extracellular vesicles in muscle wasting. Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle, 11(3), 671–684.

Vanderschueren, D., et al. (2014). Androgens and skeletal muscle. Endocrine Reviews, 35(6), 906–960.

Finkelstein, J. S., et al. (2013). Gonadal steroids and body composition in men. New England Journal of Medicine, 369(11), 1011–1022.

https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1206168

Hohenauer, E., et al. (2015). Cold-water immersion and recovery. Sports Medicine, 45(10), 1341–1351.

Hill, J., et al. (2014). Compression garments and recovery. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 28(8), 2228–2236.

McPherron, A. C., Lawler, A. M., & Lee, S.-J. (1997). Regulation of skeletal muscle mass by myostatin. Nature, 387(6628), 83–90.

Campbell, M. D., et al. (2018). Exercise mimetics and AMPK activation. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism, 29(6), 380–393.

Where is the economy shifting in healthcare? Check out Prosper for our insights.

Explore more from Issue #3: New Insights into Muscle Health

Pick the next section to read in Issue 3