Issue 3: New Insights into Muscle Health

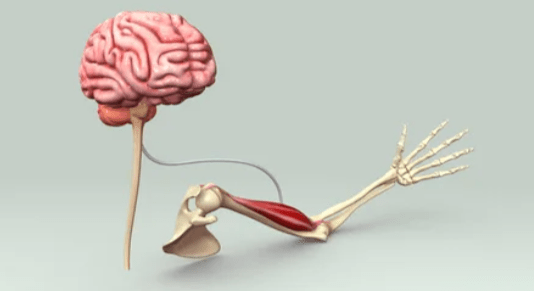

Mind Inside Muscle

Every act of movement begins as a thought.

A spark in the motor cortex crosses a web of synapses, travels down the spinal cord, and ends as contraction.

What we call strength is, at its root, neural intention made visible.

Muscle is not separate from mind — it is an extension of it.

Both arise from the same embryonic layer of excitable tissue. Both depend on the same fuels and electrical precision. When one dulls, the other often follows.

We see this in the clinic and in the mirror. The slumped posture of depression, the slowed gait of cognitive decline, the inertia of burnout — each tells the same story: when the motor system quiets, so does will.

For decades, we’ve treated movement as a by-product of thought. But neuroscience has inverted that hierarchy.

Movement feeds thought. The act of contracting muscle drives sensory feedback to the brain, sustaining alertness, neuroplasticity, and motivation.

It’s not only the brain commanding the body; it’s the body keeping the brain awake to the world.

To understand muscle health, then, is to study the mind’s most ancient extension.

And the bridge between the two — where electricity becomes intention, and intention becomes motion — is the neuromuscular junction.

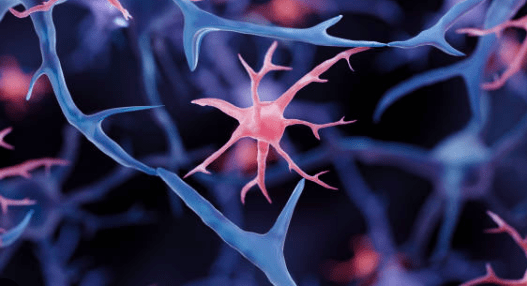

The Neuromuscular Junction — Where Intention Becomes Action

At the end of every motor neuron lies one of the most elegant structures in biology: the neuromuscular junction (NMJ).

It is the place where an idea, generated in the brain, becomes movement in the world. But this intimate dialogue between brain and body is not born fluent. It must be shaped.

The Neuromuscular Junction: Structure Before Story

Before we talk about how the neuromuscular junction (NMJ) develops, matures, or deteriorates, it helps to be precise about what it is.

The NMJ is a specialized synapse — a tightly organized communication interface between three elements:

- The presynaptic motor neuron terminal

- The synaptic cleft

- The postsynaptic muscle endplate

Each component is structurally and functionally distinct.

1. Presynaptic motor neuron terminal

This is the distal end of a lower motor neuron. It contains:

- synaptic vesicles packed with acetylcholine (ACh)

- voltage-gated calcium channels

- mitochondria to support rapid, repeated firing

The motor neuron does not “touch” the muscle fiber. Communication is chemical, not electrical.

2. The synaptic cleft

A narrow extracellular space (~50 nm wide) separating nerve from muscle.

It contains:

- acetylcholinesterase, which rapidly breaks down ACh

- extracellular matrix proteins that stabilize the junction

This space ensures signaling is brief, precise, and resettable — allowing rapid, repeated contractions.

3. The postsynaptic muscle endplate

This is a highly specialized region of the muscle fiber membrane characterized by:

- dense clustering of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (AChRs)

- deep junctional folds that increase surface area

- voltage-gated sodium channels concentrated at fold depths

These folds amplify the signal, ensuring that a single nerve impulse reliably triggers a muscle action potential.

Together, these three components form a high-fidelity biological relay — optimized for speed, precision, and repeatability.

Only then does movement acquire its characteristic clarity — smooth sequencing, graded force, intention speaking with one voice.

The NMJ Begins in Multiplicity

At birth, each muscle fiber receives input from multiple motor neurons — a state known as poly-innervation. The wiring is exuberant but imprecise. Acetylcholine receptors (AChRs) lie in broad, immature plaques. Synaptic folds are shallow. The circuit works, but it lacks the crisp timing and fidelity that mature movement requires.

Over the first weeks of life, this excess is painstakingly sculpted away.

Motor neurons compete for territory. Activity-dependent signals strengthen some synapses while eliminating others. Under the guidance of agrin, MuSK, and rapsyn (all proteins in the NMJ), AChRs cluster into tight, pretzel-like patterns. Poly-innervation collapses into the elegant adult rule: one fiber, one motor neuron.

Only then does movement acquire its characteristic clarity — smooth sequencing, graded force, intention speaking with one voice.

How the Junction Works

When the brain decides to move:

- An electrical impulse travels down the motor neuron.

- Calcium floods the nerve terminal.

- Vesicles release acetylcholine into the synaptic cleft.

- ACh binds the tightly clustered receptors on the muscle.

- Sodium rushes in, depolarizing the fiber.

- The signal dives deep into the cell via T-tubules.

- Calcium bursts from the sarcoplasmic reticulum → the fiber contracts.

This is thought becoming force — in a space the width of a dust particle

How the Junction Ages

With time, the architecture begins to loosen:

- Agrin signaling fades.

- MuSK activation declines.

- Receptors fragment and drift apart.

- Motor neurons withdraw terminal branches.

- Mitochondria at the endplate falter under oxidative stress.

Even before muscle fibers atrophy, the signal that animates them weakens. The person often feels this not as strength loss, but as hesitation — a subtle sense that the body is slower to obey.

The NMJ is the literal bridge between desire and execution, motivation and movement.

When this synapse frays, people often describe not just muscular fatigue, but a dimming of drive — as though effort itself feels heavier.

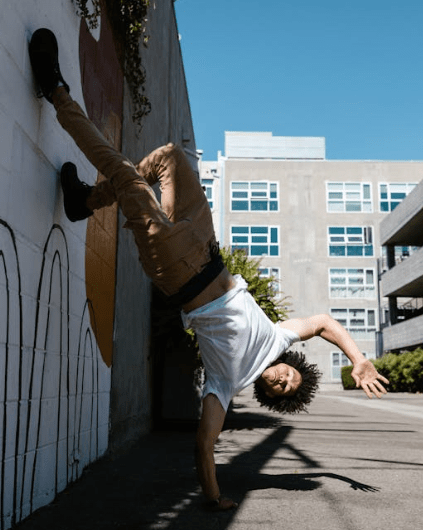

The inverse is also true: when NMJs are healthy, movement feels intuitive, fluid, expressive. This is why coordinated training, dance, and skill-based exercise can feel mentally clarifying and emotionally enlivening: they refine the synapse where brain becomes body.

The neuromuscular junction is where intention acquires form.

Reinnervation Reopens the Developmental Program

When a muscle fiber loses its neural input — through injury, aging, or disease — it does not simply reconnect. It reverts.

Sprouting axons arrive in excess. Poly-innervation returns. Receptor clusters broaden and flatten. Mitochondria at the junction become sparse and vulnerable to oxidative stress. The newly reinnervated NMJ looks, in many ways, like the neonatal one.

And just like in infancy, successful recovery depends on refinement.

Unneeded axons must withdraw. AChRs must re-cluster. MuSK signaling must re-activate. If this pruning is incomplete — as often happens in older adults — the junction remains noisy and inefficient.

What Poly-Innervation Does to Function

Recall that at birth, the NMJ is poly-innervated, and this is a hallmark of immaturity. Poly-innervation produces:

- Loss of precision: one fiber contracting under multiple, asynchronous neural commands.

- Desynchrony: adjacent fibers firing out of phase, degrading force transmission.

- Increased neuromuscular “jitter”: inconsistent latency between nerve signal and muscle response.

- Metabolic inefficiency: fibers fire redundantly, increasing ATP demand and fatigue.

To the person experiencing it, this feels not like weakness, but like hesitation — as though the body is thinking twice before obeying.

Takeaway

The NMJ is the physical site where will becomes movement. When it frays, people often describe a dulling not only of strength but of drive. A sense that effort costs more. That intention moves through molasses.

Conversely, when the NMJ is refined — through repeated, meaningful use — movement feels fluid, expressive, and mentally clarifying. This is why skill-based practice, dance, martial arts, and resistance training feel psychologically enlivening: they sharpen the interface where the self touches the world.

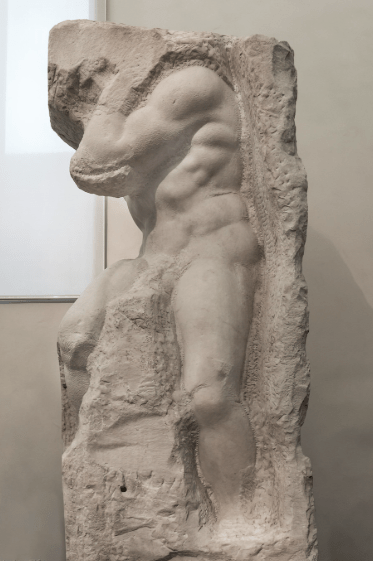

Michelangelo’s Prisoners: A Metaphor for the Developing NMJ

Michelangelo’s Prisoners — figures emerging from rough marble, half-formed but unmistakably alive — are the perfect metaphor for the neuromuscular junction at birth.

In each sculpture, the essential components of the final form are already present: the curve of a rib cage, the twist of a shoulder, the faint suggestion of motion. But they remain embedded in the block, awaiting the sculptor’s hand to release their clarity.

The neonatal NMJ is much the same.

All the pieces exist — the motor neurons, the muscle fiber, the receptors, the synaptic machinery — but they are in a primitive, overabundant state. Poly-innervated. Broad. Lacking precision.

Agrin and MuSK act like Michelangelo’s chisel, refining the raw structure into a mature, high-fidelity synapse.

Pruning removes redundant axons. Receptor clusters tighten. The junction emerges from excess into definition.

And when injury forces the adult NMJ to repair itself, it returns to this sculptural beginning — rough, poly-connected, unrefined — and must once again carve itself into singular clarity.

Just as Michelangelo believed the figure was already inside the stone, the mature NMJ is already within the early one — waiting to be shaped by activity, intention, and use.

Shared Energy Systems — Glucose, Glycogen, and Phosphocreatine as Dual Brain–Muscle Fuels

Movement and thought are metabolically inseparable. While their outputs differ — a contraction here, a concept there — their inputs are deeply shared. Both rely on the same metabolic pillars to sustain function, resilience, and identity.

We begin with the most fundamental of these fuels: glucose.

I. Glucose — The Primary Fuel for Both Brain and Muscle

Glucose is the body’s default currency of immediate energy.

Muscle: The Glucose Reservoir and Buffer

When glucose enters the circulation — from food, infusion, or glycogen breakdown — roughly 70–75% is taken up by skeletal muscle.

This is not merely disposal; it is stabilizing. Muscle protects the rest of the body — particularly the brain — from extremes in glucose swings.

Insulin-resistant muscle, by contrast, loses this buffering capacity. Blood glucose rises, insulin climbs, and metabolic volatility emerges — affecting cognition, mood, and homeostasis.

Brain: The Glucose Furnace

The brain represents only 2% of body weight yet consumes 20–25% of all glucose at rest.

Regions involved in working memory, attention, and executive function exhibit increased glucose uptake during cognitive tasks.

Unlike muscle, the brain cannot “rest” to save energy; it needs constant supply.

When glucose availability becomes erratic — from metabolic disease, poor sleep, chronic stress, or mitochondrial dysfunction — the brain’s stability falters.

People describe irritability, fog, low motivation, slow recall: metabolic symptoms disguised as psychological ones.

II. Glycogen — Stored Readiness in Both Tissues

If glucose is fast-access fuel, glycogen is strategic reserve — the difference between being able to endure and being forced to stop.

Muscle Glycogen

Muscle stores the majority of the body’s glycogen. During activity:

- it sustains repeated contractions,

- influences perceived effort,

- affects coordination and fatigue thresholds, and

- supplies lactate that can serve as an alternate fuel for other tissues.

Low muscle glycogen — whether from illness, underfeeding, overtraining, or aging — manifests as:

- heaviness,

- early fatigue,

- loss of physical confidence,

- reduced motivation to move.

Brain Glycogen (Astrocytic Stores)

Neurons cannot store glycogen. Instead, astrocytes maintain small glycogen reserves that support:

- bursts of synaptic activity,

- memory consolidation during sleep,

- metabolic stability during hypoglycemia or stress.

Astrocyte glycogen is not a supply equal to muscle’s, but it is crucial for cognitive resilience.

When sleep is inadequate, astrocytic glycogen does not fully replenish, leading to:

- slower processing,

- emotional volatility,

- reduced learning efficiency.

A Note on Lactate

Astrocytes and neurons can both produce and consume lactate.

The idea that lactate always moves from astrocytes → neurons (the “astrocyte–neuron lactate shuttle”) is intriguing but not fully validated.

Some studies support it; others contradict it. The modern view is that lactate may be:

- an auxiliary energy source under high demand or stress,

- a signaling molecule,

- context-dependent rather than universal.

(See Box: Is There Really an Astrocyte–Neuron Lactate Shuttle?)

III. Phosphocreatine — The Rapid-Response System for Thought and Movement

If glucose powers the ongoing work and glycogen powers sustained work, phosphocreatine (PCr) powers the instantaneous work — the ability to respond to intention without delay.

The ATP Buffer

Both neurons and muscle fibers rely on stable ATP levels. But ATP depletes rapidly during:

- high-frequency synaptic firing,

- rapid changes in membrane potential,

- forceful contractions.

The phosphocreatine system intervenes:

PCr + ADP → ATP + creatine

(catalyzed by creatine kinase)

This reaction occurs in milliseconds, giving cells the time they need to normalize ATP through mitochondrial respiration.

Brain PCr

When PCr stores are robust:

- cognitive work feels sharper,

- attention stabilizes,

- resilience to fatigue improves.

When PCr declines — in aging, neuroinflammation, sleep loss, or chronic stress — people experience:

- “tired brain,”

- slower working memory,

- reduced task engagement.

Muscle PCr

In muscle, PCr supports:

- repeated bursts of force,

- NMJ fidelity,

- rapid motor-unit recruitment.

Declining PCr contributes to:

- sarcopenic fatigue,

- slower contraction speed,

- decreased sense of agency in movement.

This is why creatine supplementation affects both mental and physical worlds: it strengthens the shared scaffold that underlies intention.

Is There Really an Astrocyte–Neuron Lactate Shuttle?

The astrocyte–neuron lactate shuttle (ANLS) is a well-known hypothesis proposing that astrocytes produce lactate that neurons use as fuel during heightened activity.

Why It Became Popular

- Astrocytes store glycogen; neurons don’t.

- Astrocytes have higher baseline lactate concentrations.

- Under some conditions, neurons do use lactate efficiently.

Why It’s Contested

Recent rigorous reviews — including those from the American Physiological Society — raise concerns:

- Neurons clearly increase their own glucose uptake and glycolysis under stimulation.

- Some in vivo data do not show preferential neuronal lactate use.

- Metabolic flux appears context-dependent, not fixed.

Current Consensus

The ANLS is possible, but not universal.

Brain metabolism appears flexible: sometimes neurons use lactate, sometimes glucose, sometimes both.

Why We Include This Debate

Because scientific rigor requires distinguishing between:

- Hypotheses that are elegant, and

- Hypotheses that are established.

For now, ANLS remains the former.

Phosphocreatine Supplementation — Strengthening Synapse and Muscle

Creatine is one of the most studied and reliable ergogenic compounds in physiology. But its influence extends well beyond the gym.

Because creatine feeds into the phosphocreatine (PCr) shuttle, the core rapid-response energy buffer for both neurons and myocytes, supplementing it strengthens the shared metabolic backbone of cognition and movement.

Most people think creatine only makes muscles stronger.

What they don’t know is that it often makes the mind stronger too.

I. Why Supplement Creatine at All?

Creatine is obtained from diet (meat, fish) and synthesized endogenously. Yet many people — especially older adults, vegetarians, vegans, and those under chronic metabolic stress — do not maintain optimal intracellular levels in brain or muscle.

Supplementation increases:

- brain creatine by ~5–15% (varies by tissue and baseline levels)

- muscle phosphocreatine by ~10–40%

- phosphocreatine resynthesis after exertion

- ATP buffering under cognitive and physical load

Because neurons and muscles rely on the same rapid ATP-recycling system, improving PCr availability enhances performance in both domains.

II. Evidence for Cognitive Benefits

Creatine’s effects on the brain are most pronounced under metabolic strain — periods when ATP turnover is high or recovery is limited.

1. Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Cross-Over Trial (Rae et al., 2003)

One of the most elegant demonstrations of creatine’s cognitive effects comes from a 6-week cross-over trial in vegetarians.

- 5 g/day creatine monohydrate

- improved working memory, intelligence test performance, and task accuracy

Vegetarians are a perfect test group: lower dietary creatine → larger shifts with supplementation.

2. Nature Portfolio (Scientific Reports, 2024)

A more recent human crossover study found that even a single dose of creatine improved performance on:

- attention tasks

- working-memory tasks

Effect sizes were modest but clear — confirming that creatine can influence acute cognitive energetics, not just long-term stores.

3. Meta-Analyses & Systematic Reviews

Across studies:

- greatest benefits occur under sleep deprivation, hypoxia, mental fatigue, or in older adults

- improvements cluster in short-term memory, reasoning, attention, and task consistency

- heterogeneity exists, but a pattern is emerging: creatine helps the brain when it needs help the most

This matches the physiology: the phosphocreatine system protects against energy dips — and cognition suffers most when those dips occur.

III. Evidence for Muscle & Neuromuscular Benefits

Muscle outcomes are well-established, but the nuance relevant to Psyche is this:

Creatine improves muscle performance in ways that reinforce neuromuscular fidelity:

- increased phosphocreatine stores → more stable ATP during repeated contractions

- enhanced NMJ reliability, especially under fatigue

- improved motor-unit recruitment

- decreased perceived exertion

- greater training volume → stronger stimulus for motor-cortex plasticity

In aging, creatine supplementation combined with resistance training improves:

- lean mass

- strength

- functional capacity

- type II fiber CSA (critical for power and independence)

These muscular improvements feed directly into psychological ones:

people feel more capable, more stable, more confident in their bodies.

IV. Bridging Brain and Muscle — The Shared Mechanism

What makes creatine extraordinary is that the same molecular reaction underlies its cognitive and physical effects:

PCr + ADP → ATP + creatine

Both neurons and muscle fibers rely on stable ATP levels to:

- transmit signals

- maintain membrane potentials

- support rapid repetitive work

- resist metabolic fatigue

When the phosphocreatine system is enhanced:

- neurons maintain firing precision,

- muscles maintain contraction fidelity,

- the NMJ maintains rapid transmission,

- cognitive effort becomes smoother,

- physical exertion becomes more sustainable.

Creatine is not a “brain supplement” or a “muscle supplement.”

It is an energy-stability supplement.

And energy stability is the substrate of agency.

V. Mood, Energy, and Resilience

Creatine has been explored as an adjunctive therapy in:

- major depressive disorder,

- treatment-resistant depression,

- postpartum depression,

- fatigue syndromes,

- chronic stress states.

Why would a molecule for ATP regulation affect mood?

Because mood is metabolically expensive:

- Neurotransmitter synthesis requires ATP.

- Synaptic firing requires ATP.

- Emotion regulation networks require ATP.

- Stress resilience requires ATP.

Low phosphocreatine availability tracks with:

- slower neuronal recovery after firing

- decreased dopaminergic tone

- reduced cortical excitability

- impaired executive function

- heightened perception of effort

Small RCTs show creatine improves SSRI response and reduces depressive symptoms, especially in women — possibly reflecting sex differences in brain energy metabolism.

Creatine doesn’t create motivation; it liberates it by removing biochemical bottlenecks that make the world feel heavier.

VI. Safety, Dosing, and Practical Considerations

- Standard dose: 3–5 g/day creatine monohydrate

- Loading phase optional

- Most benefits accrue after ~3–4 weeks of saturation

- Generally safe in healthy kidneys; caution or monitoring in CKD

- Hydration should be maintained

- No evidence of increased cramping or heat injury in athletes

Creatine monohydrate remains the gold standard — stable, bioavailable, inexpensive, effective.

Is 10 Grams of Creatine Dangerous? (Short Answer: No.)

This was a question I saw on an online medical forum so I thought we should address it here.

Creatine is not a stimulant, not a hormone, and not a drug. It is a nutrient with a well-characterized metabolic fate:

- Your muscles and brain have a finite creatine capacity.

Think of them as tanks that can be filled, but not overfilled.- Muscle stores ≈ 120–160 mmol/kg dry mass

- Brain stores ≈ 5–15 mmol/kg depending on region

Once these are saturated, they simply cannot take up more.

- Extra creatine is not “building up.” You pee it out.

Unused creatine → creatinine → renal excretion.

In healthy kidneys, this is straightforward and well-tolerated. - A 10 g dose is not dangerous.

In research settings:- A common loading protocol is 20 g/day for 5–7 days.

- Chronic use of 5–10 g/day has been studied for years with no renal harm in healthy individuals.

- Even long-term use in older adults and athletes shows no increase in kidney injury, no electrolyte disruption, no cramping, and no heat-illness risk.

(Gualano et al., Amino Acids; Poortmans et al., Med Sci Sports Exerc)

- Why doctors sometimes misunderstand this:

- They equate “creatinine” with kidney damage.

- They assume elevation = renal failure, forgetting that creatinine rises because creatine intake rises, not because the kidneys are failing.

- They are unfamiliar with sports physiology literature, where creatine has been studied for 30+ years.

- What actually matters is: Do you have kidney disease?

In CKD, caution is appropriate — not because creatine is toxic, but because:- baseline creatinine is already high

- excretion is reduced

- clinical monitoring is prudent

(This nuance is lost in most online discussions.)

- After saturation, 3–5 g/day maintains all benefits.

Higher doses are not “dangerous”; they’re simply wasteful, because the tissues are already full.

Bottom Line: Creatine is one of the safest, most studied compounds in human physiology. A 10 g dose is not dangerous — it is merely more than you need once your system is saturated.

If a person with healthy kidneys takes 10 g, the worst thing that happens is…

more creatinine in the urine. That’s it.

Creatinine ≠ Kidney Function (A Clarifying Guide)

Creatinine is one of the most misinterpreted lab values in modern medicine.

Its reputation as a “kidney number” has created an unfortunate reflex:

any rise → panic about renal failure.

But creatinine is not a direct measure of kidney damage.

It is a surrogate marker — and a very imperfect one.

Here’s what we need to understand:

1. Creatinine reflects muscle turnover, not just kidney filtration.

Creatinine is produced from:

- creatine in muscle,

- dietary creatine,

- ingested creatinine (e.g., cooked meats),

- and creatine supplements.

More muscle = more creatinine.

More activity = more creatinine.

More creatine intake = more creatinine.

None of these mean the kidneys are failing.

2. Small creatinine increases often reflect physiology, not pathology.

Examples of perfectly normal reasons creatinine rises:

- starting exercise

- gaining muscle

- switching to a high-protein or meat-heavy diet

- taking creatine supplements

- dehydration

- lab assay variability

Calling these “renal injury” is like calling tachycardia “heart failure” after climbing stairs.

3. What actually reflects kidney function is GFR, not creatinine alone.

Estimated GFR (eGFR) incorporates creatinine but interprets it through demographic and physiological context:

- age

- sex

- body size

- muscle mass

A creatinine increase with preserved eGFR is not kidney failure.

A creatinine increase with reduced eGFR may need evaluation.

This distinction is routinely missed.

4. Creatine supplementation raises creatinine → without harming kidneys.

Decades of research show:

- creatine raises serum creatinine slightly (expected)

- GFR remains normal

- cystatin C remains normal

- no evidence of structural renal injury in healthy individuals

In other words:

Creatine raises creatinine because it increases creatine turnover, not because it damages kidneys.

5. When creatinine is concerning

A creatinine rise is clinically relevant when accompanied by:

- declining eGFR

- abnormal urinalysis (proteinuria, hematuria, casts)

- electrolyte abnormalities

- symptoms of uremia

- structural kidney disease on imaging

Creatinine alone, in isolation, tells you very little.

6. The real risk is misinterpretation.

Patients frequently have:

- creatine supplementation stopped unnecessarily

- weightlifting discouraged

- “kidney failure” diagnoses incorrectly applied

- unnecessary nephrology referrals

This is not due to kidney physiology —

it is due to clinical cognitive error.

Bottom Line:

Creatinine is a reflection of muscle metabolism filtered by the kidney, not a direct measure of kidney damage.

An increase from exercise, diet, or creatine supplementation does not equal renal failure.

Kidney function is assessed by GFR, urinalysis, and clinical context — not creatinine alone.

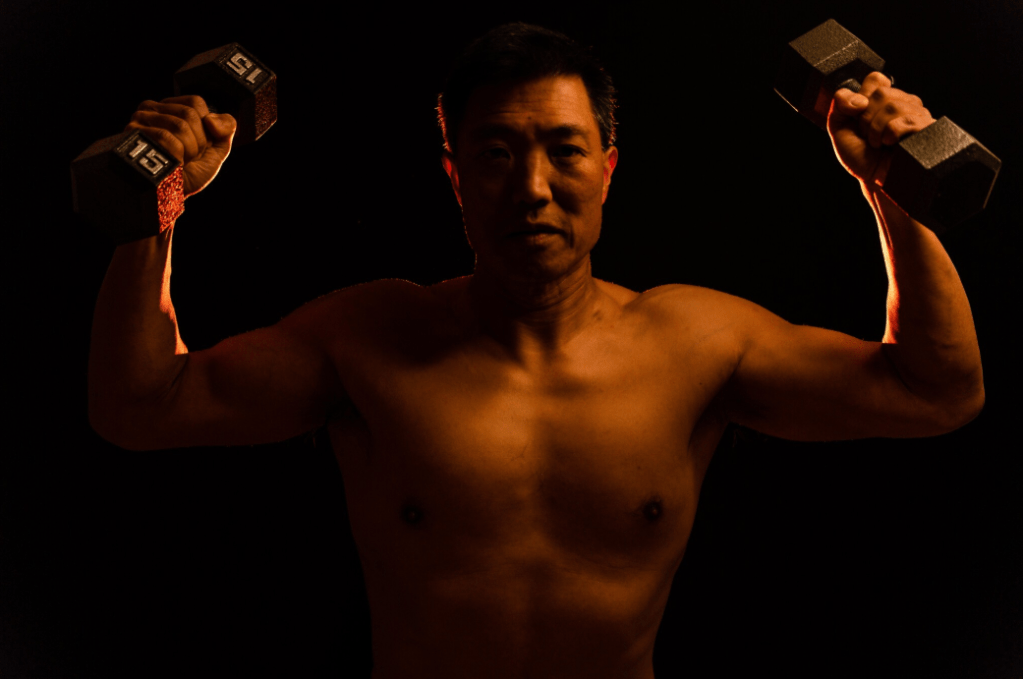

When Muscle Speaks to Mood — Five Molecular Bridges Between Strength and Mental Health

Mood is often framed as psychological, but much of mood is energetic:

a reflection of how efficiently the body makes, moves, and manages energy.

Skeletal muscle is not simply machinery for movement — it is an endocrine organ, a metabolic stabilizer, and a signal generator that speaks directly to the brain.

And when its voice weakens, the psyche feels it.

Here are five molecular bridges connecting muscle health to mental health:

1. IL-6: The Janus Molecule — Pro-Inflammatory in Fat, Anti-Inflammatory in Muscle

Most people know IL-6 as an inflammatory cytokine.

But that’s only half its identity.

Muscle-derived IL-6 (released during contraction):

- improves insulin sensitivity,

- enhances glucose uptake,

- drives anti-inflammatory pathways,

- stimulates AMPK,

- supports neuroplasticity indirectly.

In contrast, IL-6 from visceral fat:

- sustains chronic inflammation,

- worsens metabolic flexibility,

- suppresses mood-regulation circuits.

Two tissues, one molecule, opposite meanings.

When muscle shrinks, you lose the beneficial IL-6 signal — leaving the inflammatory one unopposed.

This is one reason depression, anxiety, and metabolic dysfunction frequently coexist.

2. Myokines: Muscle as a Hormone-Secreting Organ

Contracting muscle secretes >600 peptides, including:

- BDNF-like myokines that support hippocampal neurogenesis

- Irisin, which enhances energy expenditure and may support synaptic function

- Cathepsin B, linked to memory improvement

- IL-15, involved in mitochondrial function and NK-cell activity

The psychological translation of this molecular ballet is:

- better cognitive performance,

- improved emotional regulation,

- reduced allostatic load,

- increased resilience to stress.

Sarcopenia silences this endocrine symphony. Cachexia mutes it further.

3. The Metabolic Stability Pathway — Glucose, PCr, and Mitochondria

The brain’s emotional circuits rely on predictable ATP availability.

Instability — from insulin resistance, low PCr, mitochondrial dysfunction — produces:

- irritability,

- fatigue,

- cognitive fog,

- decreased reward sensitivity,

- slower prefrontal regulation of amygdala-driven responses.

Muscle acts as:

- a glucose sink,

- a glycogen reserve,

- a PCr buffer,

- an anti-inflammatory organ,

all of which stabilize brain energy.

When muscle mass decreases, the brain becomes metabolically fragile.

4. The NMJ–Motivation Loop

As we discussed earlier, the neuromuscular junction is the site where will becomes movement.

When the NMJ degrades:

- muscles fatigue sooner

- force transmission weakens

- movements feel hesitant

But subjectively, something deeper happens:

motivation erodes.

The brain begins predicting that effort will fail.

This prediction becomes self-reinforcing.

The psyche contracts.

Rebuilding NMJ integrity — through specialized resistance training, creatine, skill practice — reverses this loop.

Movement becomes credible again. Then it becomes desirable.

5. The Anti-Depressant Effect of Strength

Strength training is consistently associated with:

- reduced depressive symptoms

- improved anxiety scores

- greater self-efficacy

- increased reward responsiveness

- improved sleep architecture

Meta-analyses suggest resistance training has an effect size on mood comparable to SSRIs in some populations.

This is not surprising when you consider:

- myokines improve neuroplasticity

- phosphocreatine stabilizes neural energy

- strength improves agency

- insulin sensitivity improves glucose availability to the brain

- muscle mass reduces systemic inflammation

- the NMJ regains clarity

Strength is not just physical. It is psychological infrastructure.

How Motivation Relates to NMJ Health — The Deep Mechanistic Story

Motivation is not just psychology.

It is rooted in predictive coding and action-outcome probability — meaning your brain continuously asks: If I try…will my body follow?

The NMJ is the literal substrate of this question.

When the NMJ is degraded — fragmented, denervated, poly-innervated, misfiring — the brain receives noisy, costly, unreliable feedback. Over time, it learns: Effort does not produce the expected results.

And through classical reinforcement loops, that translates into reduced willingness to exert effort — experienced subjectively as low motivation.

This is why NMJ impairment in aging, disuse, cachexia, inactivity, and chronic disease feels like fatigue and disinterest, not just weakness.

Now let’s dive into how this has been studied and what the mechanisms look like.

1. The Action–Outcome Contingency Studies

These come mostly from motor neuroscience and behavioral economics in animals and humans.

Key Principle:

Motivation increases when the expected reward per unit of effort is predictable and reliable.

When NMJs begin to degrade:

- force production becomes inconsistent

- contraction speed slows

- firing jitter increases

- the cost of action (in ATP and subjective effort) rises

The brain detects this increased cost and automatically down-regulates effort allocation through:

- reduced dopaminergic firing in the striatum

- reduced motor-cortical excitability

- altered premotor planning

Evidence:

- Aging models show that when NMJ fragmentation begins, animals voluntarily decrease wheel running, exploration, and food-foraging tasks before measurable muscle atrophy occurs.

- When NMJs are experimentally stabilized (genetically or through training), voluntary activity increases, even without changes in muscle size.

This is the earliest clue that NMJ reliability → effort willingness.

2. Dopamine–NMJ Interlock: The “Effort Economy” Network

Motivation is heavily influenced by dopaminergic circuits.

And dopamine neurons adjust firing rates based on perceived physical cost.

Rodent studies show:

- When NMJs are partially denervated (using botulinum fragments or sciatic nerve crush), animals show decreased dopaminergic motivation to pursue rewards requiring effort, but normal interest in rewards requiring no effort.

- Conversely, when NMJ transmission is pharmacologically enhanced, dopamine-driven effort tasks improve.

This indicates that the brain is not “depressed” — it is making a rational metabolic decision: Effort is too expensive right now.

The NMJ communicates its inefficiency upstream through proprioceptive and interoceptive pathways, altering dopaminergic reward valuation.

3. Motor-Cortex Plasticity Depends on NMJ Fidelity

This one is astonishing:

Motor cortex output and willingness to initiate movement scale with the integrity of peripheral NMJs.

Studies using:

- TMS (transcranial magnetic stimulation)

- EMG latency

- paired associative stimulation

…show that when NMJs degrade:

- motor cortex excitability drops

- cortico-motor coherence weakens

- skill acquisition slows

- initiation latency increases

This affects both movement and the willingness to perform movement.

The brain reads the impaired NMJ as an unreliable effector.

When NMJs are reinnervated or strengthened through resistance training or neuromuscular stimulation, motor cortical excitability returns — and motivation increases.

This provides a neural basis for “the more I move, the more I want to move.”

4. The NMJ Fatigue–Motivation Loop

NMJs that are:

- partially denervated

- flattened

- agrin-deficient

- fragmented

- with impaired AChR clustering

…fatigue faster.

When junctions tire quickly, so does the organism.

Effort becomes aversive because effort rewards become unpredictable.

Key experimental findings:

- Mice with genetically induced NMJ fragmentation exhibit decreased voluntary activity even when muscle mass is normal.

- Once their NMJs are repaired, activity levels normalize, without changes in mood-related circuits.

This shows the “motivation drop” was muscular, not psychological.

Humans show similar patterns in early sarcopenia: Fatigue and low drive often precede visible weakness by years.

5. The Interoceptive Signal: “Can I Trust My Body?”

Your insula and ACC (anterior cingulate cortex) compute effort cost from interoceptive data.

If neuromuscular transmission is unreliable:

- effort feels heavier

- movement feels less fluid

- predictions fail

- the body feels unsafe or unwieldy

Repeated failed predictions lead the brain to reduce the “budget” for action.

This is not laziness, it is predictive homeostasis.

When NMJ efficiency improves, the interoceptive signal shifts. When the brain detects that effort “works again” (i.e. effort cost is commensurate with results), motivation increases.

This, by the way, is why:

- resistance training improves mood

- creatine improves task initiation

- physical rehabilitation increases motivation long before strength returns

You are restoring the body’s reliability, and the brain reopens the gates to action.

So… Has It Been Directly Studied in Humans?

Not with NMJ biopsies (invasive), but with:

- EMG jitter analysis

- single-fiber EMG

- voluntary activation studies

- effort-based decision-making paradigms

- TMS motor excitability testing

- aging cohorts tracking NMJ fragmentation vs. motivation

Across these methods, the pattern is consistent:

⇢ Less NMJ integrity → less voluntary effort → less motivation

⇢ More NMJ integrity → more voluntary effort → more motivation

The brain is constantly budgeting energy based on how trustworthy the body feels.

Motivation is not a character trait. It is a physiologic prediction.

And when physiology falters — NMJ reliability, energy buffering, chronic pain, inflammation, impaired force transmission — the brain lowers the expected return on effort. Motivation dips. Not because the person is weak-willed, but because the body is signaling: This might not work. Conserve energy. Protect yourself.

Has this been studied in humans in the context of exercise routines?

Yes — several lines of evidence converge on this.

Not always framed explicitly as “NMJ → motivation,” but the physiology is unmistakable.

A. Effort-Based Decision-Making Studies

These are behavioral economics tasks where humans choose between:

- high effort/high reward tasks

- low effort/low reward tasks

Findings show:

- When physical effort feels easier (better muscle function, better conditioning), people choose more effortful tasks, even outside physical domains.

- Improvements in aerobic capacity and strength correlate with increased cognitive willingness to take on demanding tasks (academic, professional, creative).

This is the NMJ → interoception → dopamine → motivation loop in action.

B. Initiating a fitness routine increases global drive

There are longitudinal studies showing that beginning an exercise routine leads to:

- increased initiative in unrelated domains

- improved goal pursuit

- enhanced task initiation

- greater self-regulation

- greater productivity

- reduced procrastination

Even walking programs show this effect.

The stronger the neuromuscular feedback, the stronger the psychological momentum.

C. TMS + Voluntary Activation Studies

Humans with impaired neuromuscular transmission (even mild) have:

- reduced motor cortex excitability

- reduced willingness to initiate voluntary action

- slower task commencement

Restoring neuromuscular function (exercise, stimulation, creatine, rehab) restores behavioral drive.

D. Chronic Pain Studies

Chronic pain reduces:

- cortico-motor excitability

- dopaminergic salience of rewards

- goal-directed behavior

This is the brain saying: Movement is uncertain, costly, unpredictable–>reduce output.

Chronic pain erodes the brain’s confidence in the body, reducing motivational bandwidth. Once pain improves, motivation returns long before personality changes.

E. Exercise-as-Interoceptive-Recalibration

One of the most robust findings in psychology:

- exercise increases motivation

- motivation increases exercise

- the mechanism is not purely endorphins or BDNF

- it is predictive interoception

The body becomes a reliable instrument.

The brain recalibrates effort cost.

Drive returns.

This is why successful people almost universally have a fitness routine:

It is not discipline → exercise.

It is physiology → discipline.

References

Sanes, J. R., & Lichtman, J. W. (2001). Induction, assembly, maturation and maintenance of a postsynaptic apparatus. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 2(11), 791–805.

https://doi.org/10.1038/35097557

Sanes, J. R., & Lichtman, J. W. (1999). Development of the vertebrate neuromuscular junction. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 22, 389–442.

https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.neuro.22.1.389

Burden, S. J., Huijbers, M. G., & Remedio, L. (2018). Fundamental molecules and mechanisms for forming and maintaining neuromuscular synapses. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 19(2), 490.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19020490

Tintignac, L. A., Brenner, H.-R., & Rüegg, M. A. (2015). Mechanisms regulating neuromuscular junction development and function and causes of muscle wasting. Physiological Reviews, 95(3), 809–852.

https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00033.2014

Tapia, J. C., & Lichtman, J. W. (2012). Synapse elimination in neuromuscular junctions. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 35, 419–443.

https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113810

Walsh, M. K., & Lichtman, J. W. (2003). In vivo time-lapse imaging of synaptic takeover associated with naturally occurring synapse elimination. Neuron, 37(1), 67–73.

Rudolf, R., Khan, M. M., Labeit, S., & Deschenes, M. R. (2014). Degeneration of neuromuscular junction in age and dystrophy. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 6, 99.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2014.00099

McMahan, U. J. (1990). The agrin hypothesis. Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology, 55, 407–418.

Glass, D. J., Bowen, D. C., Stitt, T. N., Radziejewski, C., Bruno, J., Ryan, T. E., … Yancopoulos, G. D. (1996). Agrin acts via a MuSK receptor complex. Cell, 85(4), 513–523.

Gautam, M., Noakes, P. G., Moscoso, L., Rupp, F., Scheller, R. H., Merlie, J. P., & Sanes, J. R. (1996). Defective neuromuscular synaptogenesis in agrin-deficient mutant mice. Cell, 85(4), 525–535.

Li, Y., Lee, Y., & Thompson, W. J. (2011). Changes in aging mouse neuromuscular junctions are explained by degeneration and regeneration of muscle fiber segments at the synapse. Journal of Neuroscience, 31(42), 14910–14919.

https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3590-11.2011

Hepple, R. T., Rice, C. L., & Brown, M. (2017). The aging neuromuscular system: Structural changes, function, and plasticity. Physiology, 32(4), 253–263.

https://doi.org/10.1152/physiol.00040.2016

Deschenes, M. R. (2011). Motor unit and neuromuscular junction remodeling with aging. Current Aging Science, 4(3), 209–220.

Petersen, K. F., & Shulman, G. I. (2002). Pathogenesis of insulin resistance in skeletal muscle. American Journal of Cardiology, 90(5A), 11G–18G.

Magistretti, P. J., & Allaman, I. (2015). A cellular perspective on brain energy metabolism and functional imaging. Neuron, 86(4), 883–901.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2015.03.035

Dienel, G. A. (2012). Brain lactate metabolism: The discoveries and the controversies. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism, 32(7), 1107–1138.

https://doi.org/10.1038/jcbfm.2011.175

Wyss, M., & Kaddurah-Daouk, R. (2000). Creatine and creatinine metabolism. Physiological Reviews, 80(3), 1107–1213.

Rae, C., Digney, A. L., McEwan, S. R., & Bates, T. C. (2003). Oral creatine monohydrate supplementation improves brain performance: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over trial. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 270(1529), 2147–2150.

https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2003.2492

Avgerinos, K. I., Spyrou, N., Bougioukas, K. I., & Kapogiannis, D. (2018). Effects of creatine supplementation on cognitive function of healthy individuals: A systematic review. Experimental Gerontology, 108, 166–173.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2018.04.018

Stevens, L. A., & Levey, A. S. (2009). Measurement of kidney function. Medical Clinics of North America, 93(3), 457–473.

Shlipak, M. G., Matsushita, K., Ärnlöv, J., Inker, L. A., Katz, R., Polkinghorne, K. R., … Levey, A. S. (2013). Cystatin C versus creatinine in determining risk based on kidney function. New England Journal of Medicine, 369(10), 932–943.

https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1214234

Baxmann, A. C., Ahmed, M. S., Marques, N. C., Menon, V. B., Pereira, A. B., Kirsztajn, G. M., & Heilberg, I. P. (2008). Influence of muscle mass and physical activity on serum and urinary creatinine and serum cystatin C. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 3(2), 348–354.

Fouque, D., Kalantar-Zadeh, K., Kopple, J., Cano, N., Chauveau, P., Cuppari, L., … Wanner, C. (2008). A proposed nomenclature and diagnostic criteria for protein–energy wasting in acute and chronic kidney disease. Kidney International, 73(4), 391–398.

https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ki.5002585

Souweine, J.-S., Kuster, N., Chenine, L., Rodriguez, A., & Chalopin, J.-M. (2021). Sarcopenia in chronic kidney disease: Pathophysiology and treatment. Nutrients, 13(11), 4087.

https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13114087

Volaklis, K. A., Halle, M., & Meisinger, C. (2016). Muscular strength as a strong predictor of mortality: A narrative review. European Journal of Internal Medicine, 35, 20–25.

Strickland, J. C., Smith, M. A., & Yancey, J. R. (2019). Skeletal muscle as an endocrine organ: Role in mental health. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 32(5), 388–394.

Pedersen, B. K. (2019). Physical activity and muscle–brain crosstalk. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 15(7), 383–392.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-019-0174-x

Ready to dive into the immune functions of muscle, its signaling properties and its interaction with fat? It’s all up next in Probe.

Explore more from Issue #3: New Insights into Muscle Health

Pick the next section to read in Issue 3