Issue #3: New Insights into Muscle Health

The Architecture of Muscle

Skeletal muscle is not a single substance.

It is a layered, living system — part contractile engine, part connective tissue, part metabolic organ, part neural interface.

From Whole Muscle to Molecular Machinery

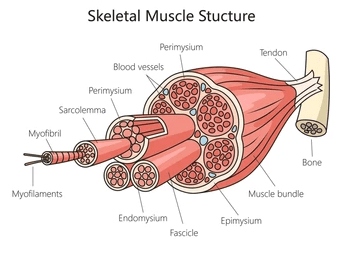

Skeletal muscle is organized like a set of Russian nesting dolls — each layer containing a smaller, more precise structure within it.

At the largest scale is the whole muscle, wrapped in a tough connective tissue sheath called the epimysium. Inside are bundles of muscle fibers known as fascicles, each encased in perimysium. Within each fascicle are individual muscle fibers — long, multinucleated cells — each surrounded by a delicate matrix called endomysium.

These connective tissue layers are not mere wrapping. They form a continuous force-transmission network, linking microscopic contraction to macroscopic movement and anchoring muscle to tendon and bone.

Open the next “doll,” and inside each muscle fiber lies a dense array of myofibrils — threadlike structures that run the length of the cell. Each myofibril is composed of repeating units called sarcomeres, aligned end to end like perfectly stacked tiles.

Sarcomeres are where force is actually generated.

Within each sarcomere, thick myosin filaments sit between thin actin filaments. When a muscle is activated, myosin heads reach out, attach to actin, and pull — like millions of microscopic hands tugging on ropes. With each pull, the actin filaments slide inward, the sarcomere shortens, and tension is produced.

When this happens in synchrony across billions of sarcomeres, the muscle shortens and force is transmitted outward through the connective tissue layers, into tendons, and finally into movement.

Strength, then, is not just about having more muscle — it is about how well these nested structures are built, aligned, activated, and connected.

Muscle Fibers Are Not All the Same

Muscle fibers differ in their metabolic and functional properties:

- Type I (slow-twitch) fibers

- high mitochondrial density

- fatigue-resistant

- optimized for endurance and postural control

- Type II (fast-twitch) fibers

- greater force and power

- more glycolytic

- critical for strength, speed, and fall prevention

Sarcopenia does not affect all fibers equally.

Fast-twitch fibers — the ones that protect us from falls and generate power — are often lost first.

Connective Tissue is Vital

When talking about strength and muscle health, the tendency in research and clinical practice is to focus on muscle fibres alone. However, the structure of whole muscle includes the layers of connective tissue wrapping for a fundamental reason.

Without connective tissue, skeletal muscle would generate force but could not transmit it effectively or coordinately. Functional movement would be profoundly impaired.

The Intramuscular Connective Tissue (IMCT is also often referred to as the ECM. Technically, the IMCT refers to the entire tissue unit, including the ECM and the cells that maintain it (such as fibroblasts). The Extracellular Matrix (ECM) is a complex, non-cellular scaffold of proteins (like collagen) and other molecules surrounding muscle fibers, providing structural support, transmitting contractile force, protecting fibers, guiding development and repair, and mediating cell signaling, acting like the “mortar” holding muscle together and allowing it to function and adapt. It’s organized into layers (epimysium, perimysium, endomysium) and is crucial for muscle integrity, regeneration, and response to exercise and disease.

Let’s unpack this here:

1. How force actually leaves a muscle fiber

When a sarcomere shortens, force is generated inside the muscle fiber. But that force has to be:

- transmitted along the fiber

- transferred out of the fiber

- coordinated across thousands of fibers

- delivered to tendon and bone

The contractile machinery itself can only do Step 1.

Everything else depends on connective tissue.

2. Two pathways of force transmission

A. Longitudinal (myotendinous) transmission

This is the classic model most people learn.

- Force travels along the length of the muscle fiber

- It reaches the myotendinous junction

- It enters the tendon

- It moves the bone

This pathway is real — but it is not sufficient to explain how muscle actually works.

B. Lateral (transverse) force transmission

This is where connective tissue becomes essential.

A substantial proportion of force generated by a muscle fiber is transmitted sideways, not lengthwise.

Here’s how:

- Actin–myosin contraction deforms the muscle fiber membrane (sarcolemma)

- Force is transmitted through costameres (protein complexes linking the cytoskeleton to the extracellular matrix)

- That force enters the endomysium

- From there, it spreads into perimysium and epimysium

- The connective tissue network distributes force across neighboring fibers and into the tendon

Experimental work suggests that 30–80% of total force transmission occurs via lateral pathways, depending on muscle type, architecture, and loading conditions.

This is not marginal; it’s foundational.

3. Why connective tissue is not optional

Force summation

Without the connective tissue matrix:

- individual fibers would contract in relative isolation

- force would not summate efficiently

- output would be weaker and poorly coordinated

Force distribution

Connective tissue:

- spreads load across fibers

- prevents overstressing individual fibers

- reduces injury risk

Without it, force would be uneven, fragile, and failure-prone.

Elastic energy storage

The ECM (extracellular matrix):

- stores elastic energy

- smooths force application

- improves efficiency (especially in walking, running, jumping)

Remove this, and movement becomes jerky, inefficient, and metabolically expensive.

4. What happens when connective tissue is impaired?

We actually have real-world examples.

Muscular dystrophies

Defects in proteins that link muscle fibers to ECM (e.g. dystrophin):

- force generation may initially be preserved

- force transmission is impaired

- muscles weaken despite intact contractile machinery

- repeated damage occurs with normal use

This shows that muscle can “work” internally but fail functionally if force transmission is compromised.

Aging and fibrosis

With aging:

- collagen becomes stiffer and more cross-linked

- ECM remodeling slows

- force transmission becomes less efficient

- muscles may feel “strong” but move poorly

This is part of why strength does not always translate into function in older adults.

5. Would movement be possible without connective tissue?

In theory:

- sarcomeres would still shorten

- ATP would still be consumed

- calcium cycling would still occur

But in practice:

- force would dissipate

- fibers would slide rather than coordinate

- tendons would receive inconsistent signals

- movement would be weak, unstable, and injury-prone

Adequate functional movement would not be possible.

Strength is not just force generation.

It is force transmission with timing, direction, and coherence.

6. Why this matters for how we think about strength

Strength is a function of muscle, tendon and matrix.

Which means:

- training that grows fibers faster than ECM (extracellular matrix) adapts increases injury risk

- slow loading, isometrics, and time-under-tension matter

- tendon and ECM adaptation are rate-limiting steps in real-world strength

Muscle is the engine.

Connective tissue is the drivetrain.

You can build horsepower endlessly — but without a drivetrain, nothing moves.

7. The ECM as the Keeper of the Stem Cell Niche

Beyond transmitting force, the extracellular matrix (ECM) serves another indispensable role: it houses and regulates the muscle stem cell niche.

Skeletal muscle regeneration depends on satellite cells — resident muscle stem cells that sit in a very specific anatomical location: between the muscle fiber membrane (sarcolemma) and the surrounding basal lamina, a specialized layer of the ECM.

This positioning is not accidental.

The ECM:

- physically anchors satellite cells in place

- maintains them in a quiescent, ready state

- provides biochemical signals that govern when they remain dormant, proliferate, or differentiate

In other words, the ECM is not just scaffolding — it is instructional.

ECM as a Signaling Environment

The basal lamina and surrounding matrix bind and present:

- growth factors (e.g., IGF-1, HGF, FGF)

- cytokines

- mechanical cues from loading and stretch

When muscle is injured or stressed:

- mechanical deformation of the ECM alters local signaling

- matrix-bound growth factors are released

- satellite cells are activated

- repair and regeneration begin

If the ECM is degraded, fibrotic, excessively stiff, or poorly remodeled, this signaling environment becomes distorted.

Satellite cells may:

- fail to activate

- proliferate but not differentiate

- preferentially adopt fibrotic or adipogenic fates

This is one reason aging muscle can contain stem cells that are present but ineffective.

Why This Matters for Muscle Health and Recovery

With aging, chronic inflammation, and inactivity:

- ECM composition changes

- collagen cross-linking increases

- matrix stiffness rises

- stem cell signaling becomes dysregulated

The result is impaired repair, slower adaptation, and progressive muscle loss — even when training and nutrition are adequate.

Muscle loss, then, is not just a failure of muscle fibers to grow.

It is also a failure of the microenvironment that tells muscle how to repair itself.

The Neural Interface: Muscle Is Never “Just Muscle”

Muscle contraction is impossible without the nervous system.

Each muscle fiber is innervated at a neuromuscular junction (NMJ), where a motor neuron releases acetylcholine to trigger contraction.

A single motor neuron and all the fibers it controls form a motor unit.

Strength, precision, and coordination depend not only on muscle size, but on:

- motor-unit recruitment

- firing frequency

- synchronization

Loss of neural input leads to muscle atrophy — even if nutrition is adequate. This is one reason sarcopenia is as much a neuro-muscular disease as a muscular one.

Muscle as a Metabolic and Signaling Organ

Beyond movement, muscle plays a central role in whole-body physiology:

- it is the largest site of glucose disposal

- a major reservoir of amino acids

- an active endocrine organ that releases myokines (e.g., IL-6, IL-15, irisin)

Through these signals, muscle communicates with:

- liver

- adipose tissue

- bone

- immune cells

- brain

When muscle mass or function declines, these signaling networks are disrupted — with consequences far beyond strength alone.

Why This Matters

A quiet epidemic has been spreading across borders, often unseen until it’s irreversible.

By current estimates, 10–16% of adults over 60 worldwide live with a condition called sarcopenia (from the Greek for “deficiency in flesh”). In the United States, prevalence rises from ~10% in adults over 65 to nearly 50% by the eighth decade. In Asia, rates range from 6% in community-dwelling Chinese adults to upward of 20% in Japan and Korea, depending on criteria used. In Europe, where the term originated, pooled estimates hover near 11%, while Latin American and African studies reveal both under-diagnosis and rapid acceleration with urbanization.

Sarcopenia is not simply “shrinking muscle.”

It reflects:

- loss of muscle fibers

- impaired contractile machinery

- infiltration of fat and fibrosis

- deterioration of neuromuscular junctions

- altered metabolic and immune signaling

In other words, sarcopenia is a failure of architecture, communication, and recovery — not just a failure of bulk.

With that architecture in mind, we can now ask: What happens when this system begins to unravel — and why does it matter so much?

Defining the Disorder

According to the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP2, 2019), sarcopenia is defined as: A progressive and generalized skeletal-muscle disorder associated with increased likelihood of adverse outcomes including falls, fractures, physical disability, and mortality.

In the past, the emphasis has been on preserving or increasing muscle mass, but the limitations of this approach has become apparent: increased mass often does not translate to increased strength. And since we know that muscle’s main role is to help us function better in our daily lives, the focus has changed.

Diagnosis now centers on muscle strength as the primary parameter, with muscle quantity/quality and physical performance as confirmatory measures. The shift from “mass” to “function” reflects a deeper truth: a large muscle is not always strong, healthy or useful.

Mass vs Quality

For decades, clinicians quantified muscle the way economists once measured prosperity: by size alone. DXA and bioimpedance could estimate “lean mass,” but not whether that tissue was functional, fibrotic, or infiltrated with fat. The new frontier is muscle quality — its contractile power, mitochondrial density, and metabolic fidelity.

How we measure quality:

- Ultrasound echo intensity: brighter images imply fatty or fibrotic infiltration.

- CT or MRI attenuation: lower radiodensity = more intramuscular fat, less oxidative capacity.

- Bioelectrical phase angle or creatine-to-cystatin C ratio: biochemical proxies for cell integrity and density.

- D₃-Creatine dilution method: a small oral dose of stable-isotope creatine (^2H₃-creatine) is given; its urinary appearance after conversion to creatinine reflects the body’s total creatine pool — and thus whole-body skeletal-muscle mass.

- Advantages: direct, radiation-free, sensitive to short-term change.

- Limitation: currently research-grade, not yet routine, but rapidly advancing toward clinical use.

High-quality muscle produces force efficiently, clears glucose rapidly, and secretes myokines that coordinate immunity and bone metabolism. Low-quality muscle consumes oxygen but yields little power — a biological debt spiral.

Ethnic and ancestral variation:

- East Asian: lower absolute mass → higher apparent prevalence when Western cut-points applied.

- South Asian: higher visceral and intramuscular fat despite moderate body weight — a “thin-fat” phenotype.

- People of African descent: greater bone and muscle mass but comparable frailty risk due to lifestyle and comorbidity patterns.

- European / North-American cohorts: wide variance driven more by metabolic health than heritage.

In short, sarcopenia is not an artifact of aging but of adaptation. Even if mass is rebuilt, quality is what makes muscle intelligent tissue. It’s not just how much muscle you have, but how well it listens to metabolic and functional instruction.

The Biology of Anabolic Resistance

The tragedy of aging muscle is not simply that it shrinks, but that it stops responding. Signals that once provoked growth — a protein-rich meal, a good lift at the gym, a surge of insulin — still arrive on cue, yet the cell’s machinery responds weakly. This blunted response is anabolic resistance.

At its core, anabolic resistance represents a breakdown in communication between anabolic stimuli (nutrients, hormones, mechanical load) and the intracellular translation machinery that drives protein synthesis. In young muscle, amino acids rapidly activate mTORC1 (see below), stimulating new myofibrillar proteins within hours. In older or chronically inflamed muscle, the same signal fizzles.

What Drives Anabolic Resistance

- Chronic inflammation: Elevated IL-6, TNF-α, and CRP interfere with mTOR and insulin-signaling pathways.

- Hormonal decline: Lower testosterone, estrogen, GH, and IGF-1 reduce anabolic cues and satellite-cell activation.

- Mitochondrial dysfunction: Decreased ATP availability diverts energy toward cell defense rather than growth.

- Physical inactivity: Even ten days of bed rest can erase a decade of strength gains.

- Protein-timing gap: Older adults often consume most of their protein at dinner, missing the even distribution that optimizes synthesis.

To re-sensitize this system, loading must be mechanical and metabolic. Resistance exercise, adequate protein, sleep, and anti-inflammatory nutrition together restore the signal-to-noise ratio of growth.

mTOR — Builder, Braker, and the Longevity Paradox

mTOR (mammalian Target of Rapamycin), the body’s master translator of growth, is a cellular platform for protein synthesis.

When amino acids — especially leucine — and mechanical tension converge with insulin and IGF-1, mTOR orchestrates protein synthesis and cell repair. It is the yes signal of the muscle cell.

But longevity enthusiasts have turned the pathway into a philosophical battleground. In animal models, chronic mTOR inhibition with drugs like rapamycin extends lifespan, mimicking caloric restriction and boosting autophagy. Off-label human users now micro-dose or pulse rapalogs in pursuit of the same effect.

The irony: suppressing mTOR too aggressively may protect cells while negatively impacting function. Continuous inhibition flattens muscle-protein synthesis, delays wound healing, and amplifies anabolic resistance.

Intermittent or tissue-specific modulation may one day reconcile growth and repair, but the data remain early.

Takeaway:

Longevity is not just the inhibition of growth; it’s the rhythm between restraint and rebuilding.

Cachexia — When the Body Consumes Itself

If sarcopenia is the quiet fade of strength, cachexia is the body turning upon itself.

It is not simple starvation; food alone cannot fix it. The physiology rewires—metabolism accelerates, inflammation burns unchecked, and muscle becomes fuel for survival.

The Syndrome We Keep Missing

Cachexia is a complex metabolic syndrome marked by severe loss of skeletal muscle—with or without fat loss—that cannot be fully reversed by nutrition and leads to functional decline.

It emerges in cancer, heart failure, chronic kidney disease, COPD, and advanced inflammatory conditions such as IBD or rheumatoid arthritis.

Despite its prevalence, cachexia often hides in plain sight.

Clinicians chase the primary disease—tumor, failing heart, scarred lung—while the body’s composition quietly collapses.

- Weight alone misleads: edema and obesity can conceal profound muscle loss.

- Screening is rare: few clinics routinely assess muscle mass or quality.

- Documentation lags: weight loss is listed as a symptom rather than a secondary pathology.

The Scale of the Problem

- Cancer: affects up to 70 % of advanced cases; causes roughly 20–30 % of cancer deaths.

- Heart failure: 10–20 % meet cachexia criteria; rates can reach 31 %, doubling mortality risk.

- COPD: 20–25 % develop cachexia, independent of lung function.

- CKD: “protein-energy wasting” affects 20–40 % on dialysis.

- IBD and chronic inflammation: cytokine-driven muscle and bone loss despite adequate intake.

Across these illnesses, the same signature appears: inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β), mitochondrial inefficiency, and suppressed anabolic signaling—an acceleration of the sarcopenic process, now weaponized.

Metabolic Heat Loss: When Fat Burns the Body

Cachexia is not only a disease of muscle loss; it is also a disease of metabolic wastefulness.

Inflammatory and tumor signals such as PTH-related peptide (PTHrP) and zinc-α₂-glycoprotein (ZAG) convert energy-storing white fat into thermogenic beige/brown fat. These newly “browned” adipocytes express UCP-1 (uncoupling protein-1), which allows mitochondria to release energy as heat instead of capturing it as ATP.

The result is a hypermetabolic state—the body literally burns itself from within, expending calories even at rest.

The bone marrow amplifies this process. In chronic inflammation, marrow adipocytes expand and secrete IL-6, IL-8, and leptin, fueling systemic inflammation. Experimental work suggests marrow-derived progenitors can migrate outward, encouraging further browning of peripheral fat while simultaneously suppressing muscle regeneration.

What begins as an adaptive immune response becomes a self-sustaining metabolic fire: marrow inflammation → fat browning → energy loss → deeper muscle catabolism.

Spotlight: Cancer Cachexia

Cancer cachexia exemplifies the paradox of modern oncology: we can shrink tumors while patients still waste away.

Prevalence & Impact

Up to 70 % of those with advanced malignancy experience measurable cachexia, and roughly one in five cancer deaths result directly from metabolic wasting rather than tumor load.

Mechanisms

Tumor-derived factors such as proteolysis-inducing factor (PIF) and lipid-mobilizing factor (LMF) activate NF-κB and the ubiquitin–proteasome system, accelerating muscle breakdown while cytokines sustain systemic inflammation.

Detection

Modern imaging now turns routine scans into metabolic assessments.

Radiologists can measure cross-sectional muscle area and density at the L3 vertebra on CT images originally ordered for staging or surveillance.

Low muscle attenuation (≈ < 41 HU in women, < 33 HU in men) indicates intramuscular fat infiltration and predicts shorter survival.

These “opportunistic” CT analyses transform existing imaging into a new kind of vital sign.

Emerging Biomarker — The D₃-Creatine Dilution Test

Nearly all of the body’s creatine is stored inside skeletal muscle, where it buffers energy for contraction.

Each day, a small portion of that creatine spontaneously converts into creatinine, which is excreted in the urine at a constant rate.

Because this conversion rate is stable, the amount of creatinine that appears reflects the total size of the muscle’s creatine pool.

The test introduces a trace of harmless, heavy-labeled D₃-creatine by mouth.

It mixes evenly with the body’s existing creatine in muscle.

Over the next 24 hours, a fraction naturally degrades into D₃-creatinine, which can be detected in a urine sample.

By measuring how much labeled creatinine appears, scientists can calculate the total creatine pool—and from that derive whole-body skeletal-muscle mass directly.

Because it measures the metabolic reservoir inside the muscle itself, the method is independent of hydration status, edema, or body fat, making it far more precise than DXA or bioimpedance estimates.

It is currently used mainly in research settings but is rapidly approaching clinical readiness for diagnosing sarcopenia and tracking cachexia.

Clinical Frontiers

Early-stage therapies combine resistance training, omega-3 supplementation, ghrelin analogs (anamorelin), anti-IL-6 antibodies, and leucine-rich nutrition. Yet most oncology protocols still overlook the muscle as a treatable organ.

Spotlight: Cardiac Cachexia

In heart failure, muscle loss becomes both symptom and accelerator of decline.

Prevalence & Prognosis

Roughly one in five patients with chronic heart failure develops cachexia, and its presence doubles mortality risk, independent of ejection fraction.

Mechanisms

Reduced cardiac output causes gut congestion and malabsorption, while catecholamines and angiotensin II raise metabolic rate.

Chronic elevations of TNF-α and IL-6 suppress appetite and protein synthesis, further worsening muscle catabolism.

Clinical Signs

Weight loss > 5–6 %, progressive weakness, fatigue, and often paradoxical edema that masks the wasting beneath.

Therapeutic Approaches

Exercise rehabilitation, beta-blockers and ACE inhibitors to blunt catabolism, optimal protein intake, and omega-3 or creatine supplementation. Pilot studies show that targeting inflammation and anabolic pathways together can restore lean mass and improve quality of life.

Takeaway: Muscle decline may accelerate the end-stage of heart disease (and indeed, any chronic disease).

The Fat–Muscle–Bone Axis — The Body’s Forgotten Organ System

Fat, muscle, and bone are not separate entities—they are an integrated neuro-immune-endocrine organ system, conducting a continuous biochemical dialogue that shapes metabolism, resilience, and even mood.

Muscle: The Endocrine Engine

Skeletal muscle secretes more than strength. Its myokines—such as IL-15, irisin, myostatin, and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)—signal to the liver, pancreas, adipose tissue, and brain. Some promote growth and insulin sensitivity; others regulate immune tone and neural plasticity.

Every contraction is a molecular message: I am alive and adapting.

Fat: The Metabolic Messenger

Adipose tissue, far from inert, responds with its own vocabulary of adipokines—leptin, adiponectin, resistin, TNF-α.

When healthy, these signals modulate appetite, thermogenesis, and inflammation.

When chronic stress or overnutrition take hold, the message shifts from communication to alarm: macrophage infiltration, cytokine release, and impaired insulin signaling.

In cachexia, the pendulum swings the other way—fat burns itself through pathologic browning, contributing to energy loss rather than storage.

Bone: The Silent Conductor

Bone is not just scaffolding; it is an endocrine organ that secretes osteocalcin and FGF-23, both influencing glucose metabolism, testosterone production, and muscle growth.

Bone marrow sits at the crossroads of immunity and energy. When inflamed, it expands its fat depot and releases cytokines that fuel systemic catabolism.

In the healthy state, mechanical loading from muscle preserves bone density and keeps marrow fat quiet; when muscle atrophies, bone and marrow join the inflammatory chorus.

The Integrated Axis

Together, these three tissues form a feedback loop of mechanical force and molecular signal.

When one node fails—muscle loss, marrow inflammation, or adipose dysfunction—the entire axis destabilizes.

That collapse is what lies beneath the epidemic of “metabolic diseases” we try to treat in isolation: diabetes, osteoporosis, obesity, depression.

You cannot talk about cardiometabolic health without talking about body composition.

To restore metabolism, you must restore the conversation between fat, muscle, and bone.

There’s more: Sarcopenia and cachexia are not only biochemical disorders; they are existential ones. When the body loses strength, the mind often follows—motivation wanes, mood darkens, and identity begins to fray.

The next section, Psyche, turns inward: to the emotional weight of wasting, the neurobiology of willpower, and how regaining muscle may also mean re-inhabiting the self.

References

Cruz-Jentoft, A. J., Bahat, G., Bauer, J., Boirie, Y., Bruyère, O., Cederholm, T., … Zamboni, M. (2019). Sarcopenia: Revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age and Ageing, 48(1), 16–31.

https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afy169

Shafiee, G., Keshtkar, A., Soltani, A., Ahadi, Z., Larijani, B., & Heshmat, R. (2017). Prevalence of sarcopenia in the world: A systematic review and meta-analysis of general population studies. Journal of Diabetes & Metabolic Disorders, 16, 21.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s40200-017-0302-x

Ethgen, O., Beaudart, C., Buckinx, F., Bruyère, O., & Reginster, J.-Y. (2017). The future prevalence of sarcopenia in Europe: A claim for public health action. Calcified Tissue International, 100(3), 229–234.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-016-0220-9

Goodpaster, B. H., Park, S. W., Harris, T. B., Kritchevsky, S. B., Nevitt, M., Schwartz, A. V., … Newman, A. B. (2006). The loss of skeletal muscle strength, mass, and quality in older adults: The Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. Journal of Gerontology: Medical Sciences, 61(10), 1059–1064.

Delmonico, M. J., Harris, T. B., Visser, M., Park, S. W., Conroy, M. B., Velasquez-Mieyer, P., … Goodpaster, B. H. (2009). Longitudinal study of muscle strength, quality, and adipose tissue infiltration. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 90(6), 1579–1585.

https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2009.28047

Silventoinen, K., Magnusson, P. K. E., Tynelius, P., Kaprio, J., & Rasmussen, F. (2008). Heritability of body size and muscle strength in young adulthood: A study of one million Swedish men. Genetic Epidemiology, 32(4), 341–349.

Lear, S. A., Humphries, K. H., Kohli, S., & Frohlich, J. J. (2007). Visceral adipose tissue accumulation differs according to ethnic background: Results of the Multicultural Community Health Assessment Trial (M-CHAT). American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 86(2), 353–359.

Gallagher, D., Deurenberg, P., Wang, Z., Heymsfield, S. B., & Pi-Sunyer, F. X. (1996). Organ-tissue mass measurement allows modeling of REE and metabolically active tissue mass. American Journal of Physiology, 271(2), E249–E260.

Cuthbertson, D., Smith, K., Babraj, J., Leese, G., Waddell, T., Atherton, P., … Rennie, M. J. (2005). Anabolic signaling deficits underlie amino acid resistance of wasting, aging muscle. FASEB Journal, 19(3), 422–424.

https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.04-2640fje

Breen, L., & Phillips, S. M. (2011). Skeletal muscle protein metabolism in the elderly: Interventions to counteract the ‘anabolic resistance’ of ageing. Nutrition & Metabolism, 8, 68.

https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-7075-8-68

Saxton, R. A., & Sabatini, D. M. (2017). mTOR signaling in growth, metabolism, and disease. Cell, 168(6), 960–976.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2017.02.004

Kimball, S. R., & Jefferson, L. S. (2006). Signaling pathways and molecular mechanisms through which branched-chain amino acids mediate translational control of protein synthesis. Journal of Nutrition, 136(1 Suppl), 227S–231S.

Wolfson, R. L., Chantranupong, L., Saxton, R. A., Shen, K., Scaria, S. M., Cantor, J. R., & Sabatini, D. M. (2016). Sestrin2 is a leucine sensor for the mTORC1 pathway. Science, 351(6268), 43–48.

https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aab2674

Fearon, K., Strasser, F., Anker, S. D., Bosaeus, I., Bruera, E., Fainsinger, R. L., … Baracos, V. E. (2011). Definition and classification of cancer cachexia: An international consensus. The Lancet Oncology, 12(5), 489–495.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70218-7

Tisdale, M. J. (2009). Mechanisms of cancer cachexia. Physiological Reviews, 89(2), 381–410.

https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00016.2008

Anker, S. D., Sharma, R., & Coats, A. J. S. (2009). Cachexia in chronic disease: From mechanisms to management. The Lancet, 373(9664), 1733–1740.

Prado, C. M., Lieffers, J. R., McCargar, L. J., Reiman, T., Sawyer, M. B., Martin, L., & Baracos, V. E. (2008). Prevalence and clinical implications of sarcopenic obesity in patients with solid tumours of the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts. The Lancet Oncology, 9(7), 629–635.

Baxmann, A. C., Ahmed, M. S., Marques, N. C., Menon, V. B., Pereira, A. B., Kirsztajn, G. M., & Heilberg, I. P. (2008). Influence of muscle mass and physical activity on serum and urinary creatinine and serum cystatin C. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 3(2), 348–354.

Clark, R. V., Walker, A. C., Miller, R. R., O’Connor-Semmes, R., Ravussin, E., Cefalu, W. T., … Kraus, W. E. (2014). Creatine (methyl-d₃) dilution in urine for estimation of total body skeletal muscle mass: Accuracy and variability. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 100(4), 1047–1053.

https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.113.080879

Argilés, J. M., Busquets, S., Stemmler, B., & López-Soriano, F. J. (2014). Cachexia and sarcopenia: Mechanisms and potential targets for intervention. Current Opinion in Pharmacology, 22, 100–106.

Craft, C. S., Robinson, M. E., & Katzman, W. B. (2018). Bone marrow adipose tissue: A neglected contributor to skeletal health. Current Osteoporosis Reports, 16(5), 541–549.

Bredella, M. A., Fazeli, P. K., Miller, K. K., Misra, M., Torriani, M., Thomas, B. J., … Klibanski, A. (2009). Increased bone marrow fat in anorexia nervosa. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 94(6), 2129–2136.

Karsenty, G., & Olson, E. N. (2016). Bone and muscle endocrine functions: Unexpected paradigms of inter-organ communication. Cell, 164(6), 1248–1256.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.043

Pedersen, B. K., & Febbraio, M. A. (2012). Muscles, exercise and obesity: Skeletal muscle as a secretory organ. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 8(8), 457–465.

https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2012.49

What is the relationship between muscle and the brain? How does muscle affect mood and motivation? Find out in Psyche.

Explore more from Issue #3: New Insights into Muscle Health

Pick the next section to read in Issue 3

Evidence Distilled. Action Amplified.